Covid-19 track and trace app design – Perfection or Participation?

Foreword

At ELSE we dedicate time to R&D and self-initiated projects with varying themes. The following piece is the output of one such project, investigating the challenge of fostering participation in a Track and Trace system.

Introduction

Over the past 6 months, countless articles have discussed the UK’s Track and Trace app – first lauding it as our potential saviour, offering a return to normality, then dissecting in detail the failings of the UK’s approach. The focus of these articles has mainly been the technical workings or privacy implications of the app, but what has often been overlooked is the crucial aspect of adoption.

Technically, you can have the best app in the world, or the most ethical, but if no-one understands its value and subsequently downloads it, then it’s all wasted effort. To make adoption a success, we need to ask two key questions:

- Why would someone be motivated to download the app in the first place?

- And what might motivate them to use it regularly?

Here we discuss the behavioural change needed to make an app like this a success. Adoption doesn’t happen by chance — only as part of a carefully orchestrated process, considered from the outset.

Design for adoption

One option for mass adoption is to mandate it at a state level, forcing people to use it. While this approach might work in China, it would not be deemed an acceptable solution here (in the UK). The less draconian option is to motivate people to use it of their own accord — a nuanced approach delivering a blend of ‘carrots and sticks’.

In broad terms, success for any Track and Trace app is directly tied to the percentage of the population actively using it: the greater the percentage, the greater the accuracy of the results. The value of the system increases with each additional user added. Harnessed correctly, this increase in value from an increase in participation can be a powerful tool for adoption. Called Network Effects, it’s the same theory that drives the usefulness and growth of social networks such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

To successfully reach the greatest number of people, you need to design your solution with some key principles in mind:

Make it attractive

Be clear with the benefits, and frame them in a way that motivates people to participate.

Keep it open

Foster trust and confidence through transparent design, allowing the community to shape the output and being open about any inner workings.

Make it easy for all

Design a very low barrier to entry and connect to a wider ecosystem by leveraging existing infrastructures.

Delivering against these principles can help unlock powerful solutions to what is a behavioural problem.

Make it Attractive

Motivate me

Intrinsic motivation is the drive to complete a task because it provides personal fulfilment, regardless of any tangible reward. When it comes to participating in a Track and Trace system there will be individuals intrinsically motivated to take part. No matter what rewards are or aren’t offered they want to be a part of the solution and are likely to be driven to act towards the greater good.

Unfortunately, despite the obvious benefits to public health, many people do not have the intrinsic motivation to take part. For these reluctant users, external nudges and additional reasons to engage will be the difference between them using or not using the app. Instead of using personal health as a driving motivation, leaning on the motivation of not being a team player could be stronger. Presenting things as a case of letting the side down or, worse still, putting others in danger.

This is the kind of behaviour change problem we specialise in at ELSE. One way we approach such problems is with the Mindspace framework. Designed by the government institute for creating public policy, the model defines nine key ingredients for influencing human behaviour.

Below we’ve focused on the role the first four could have in a Track and Trace System.

Messenger and Norms

People are strongly motivated by ‘Social Proof’ the psychological and social phenomenon where people copy the actions of others in an attempt to undertake the ‘right’ behaviour in a given situation. Essentially this means people often copy those they like and are surrounded by. If the people I trust like something or act a certain way, then I am motivated to replicate. The potency of Social Proof depends on the person I observe doing an action: ‘The Messenger’ as well as the frequency I observe the action, i.e. do I perceive it socially as ‘The Norm’? When it comes to building networks, social proof can be and is intentionally leveraged to drive participation and engagement. It’s the driving force behind likes and reactions on social media because posts with more likes and comments are proven to receive greater engagement levels.

Our Recommendations:

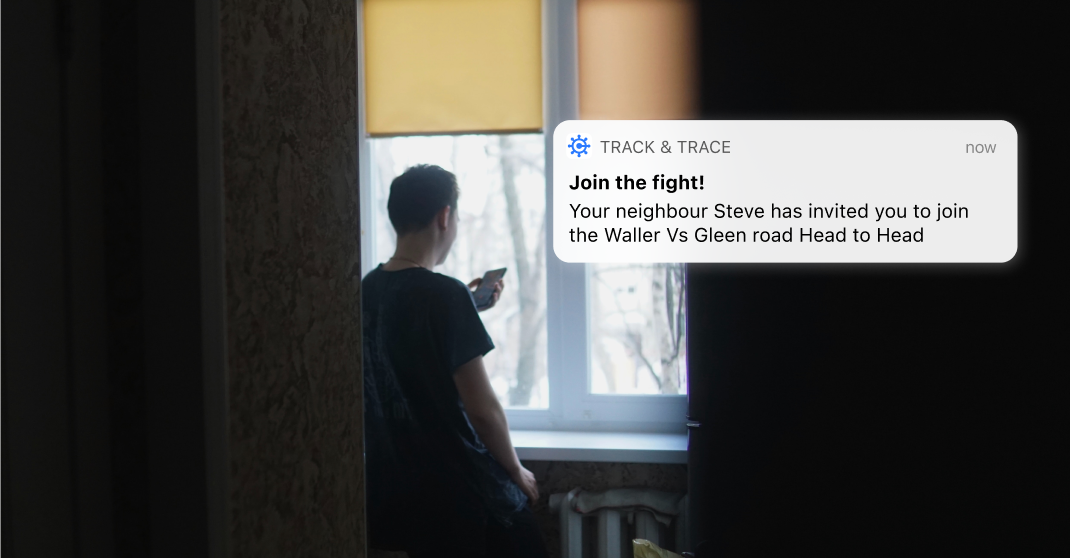

In order to leverage Social Proof, we have to make one user’s participation in the system visible to other potential users. This could be done through integration with existing social media platforms, allowing users to share sign-ups or check-ins (like foursquare). Or this could take on the form of a tag, a badge or a post used to publicise an individual’s commitment to the system. Offering referral rewards encourages users to prompt their friends to join, making participation even more visible.

Incentives

Extrinsic motivation is often defined as the drive to complete a task because of the prospect of a tangible reward or the avoidance of punishment. It’s been shown that extrinsic motivators are good for encouraging ‘algorithmic tasks’ – those that depend on following an existing formula to its logical conclusion, such as logging your activity on a COVID-tracing app. Therefore incentivisation could prove an effective method for driving participation in this system. When it comes to incentivising participation there are two approaches: the ‘Carrot’ and the ‘Stick’. The ‘Carrot’ refers to rewarding participation and is employed by many successful apps. Alternatively, the ‘Stick’ refers to punishment for non-participation. Punishment, in this case, most likely means a restriction on normal activity, for example not being allowed to enter a pub.

Our Recommendations:

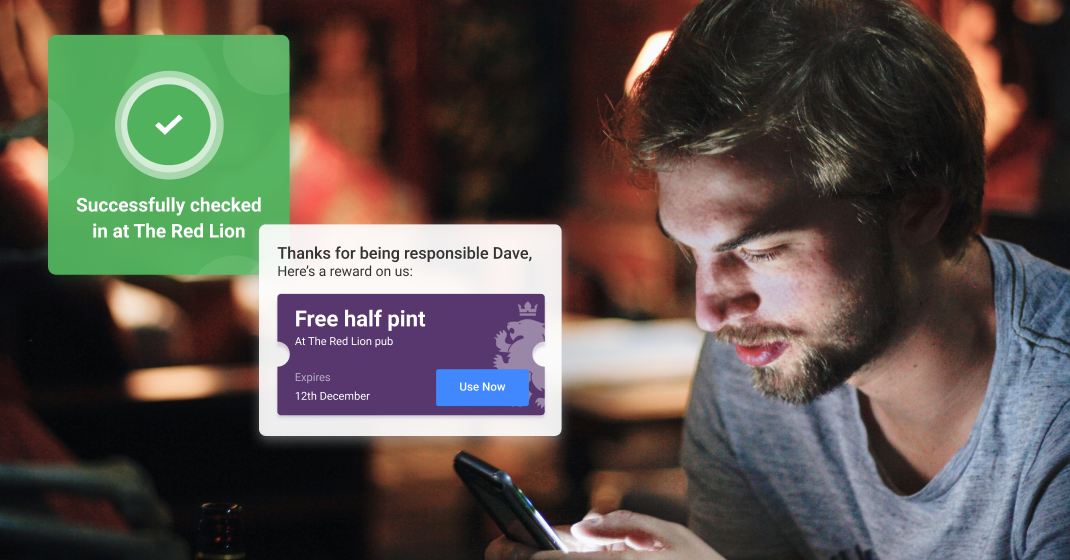

Checking or tapping-in at a place could give you a random coupon for that pub, restaurant or shop, or even one you’ve checked in with before. The ‘Eat out to help out’ scheme could have been redeemable only through the COVID-tracing app – made possible only by checking-in to that restaurant and unlocking a code.

Defaults

Many decisions we make every day have a default option, whether we recognise it or not. Defaults are the options we pre-select if we don’t make an active choice. We would argue that we humans are intrinsically lazy, and often tend to ‘go with the flow’. One famous example is the opt-out of organ donation policies which increase participation tenfold over their opt-in counterparts. When it comes to using defaults for good, public policymakers need to select the no-action outcome that maximises benefits for citizens. This way they can influence behaviour without restricting individual choice. In the context of Covid-19, this poses the question: how might we make participation the default option?

Our Recommendations:

The most obvious way defaults could be used in this context is by making participation in the system opt-out. Currently, the joint Apple and Google system for contact tracing using bluetooth is opt-in, making the no-action outcome non-participation. If contact tracing participation acts anything like organ donation, this change could lead to a massive increase in participation.

Alternatively, ‘going with the flow’ can be used in our favour. Currently, most pubs and restaurants require food and drink to be ordered through an app — reducing contact between customers and staff. By adding a check-in wall into this process, which is hard to bypass, we can start to make participation the low-effort choice.

This might look like restaurants, pubs or shops are not letting customers make a purchase, or enter their premises, without checking-in through the system. This kind of system could be the prerogative of businesses themselves or (using the incentives described earlier) could be encouraged top-down by the government. The current tax-breaks and financial aid the government is giving to businesses could be accessible only to those who encourage this type of behaviour.

Keep it open

Transparent by design

One of the key barriers to adoption is a lack of confidence in the system, or a lack of confidence in the people making key decisions — for an app that could potentially hold sensitive data about you, it’s key that we have complete trust in the system and how that data is processed.

Community-owned

Clap for carers — which easily and quickly received nation-wide participation — wasn’t started by the government, but by an individual who wanted to bring people and communities together to say thank you. Also, the Zoe C-19 app had an incredible rate of adoption, leveraging the concept of citizen science. People felt a part of the scientific endeavour. Both resulted in a feeling of collective ownership and very high participation rates — these were movements that people valued being a part of.

A feeling of ownership in the outcome is an important element of building trust. If people know that their input counts, even in a small way, then they will feel more willing to stand behind the success of a project. To maximise trust, it’s important to engage with the community who will ultimately be the judge of the product through their usage — they must be allowed to feel like they have a direct hand in shaping it.

Our recommendations:

Work to keep the broader community engaged and involved from the very start of the process, so they start to feel some element of collective ownership and are having an impact on the final outcome.

Obviously, there are logistical limitations in speaking to all 67M people in the UK, but pinpointing relevant stakeholders and opinion leaders that cover off most subsets of the population will go a long way towards making people feel like their concerns are being heard. There’s a balance in this type of engagement in terms of speed of development and consensus, but with the right framework, it will be possible.

Another aspect to make people feel involved is to be very transparent about the road map, what features will be launched and when new capabilities are due. An open road map allows people to input their thoughts or suggestions, supporting that feeling of shaping the final output.

Open collaboration and expert review

Within the UK there’s no shortage of the expert skillsets required to deliver an app like this. These experts can be very useful to build credibility. Whether it’s tapping into their skills to help with design and build, or making sure the code is available online for anyone to be able to peer-review.

Mobilising unpaid help from people might seem counter-intuitive, but being driven to complete a task or do a job because it provides personal fulfilment beyond monetary or social rewards, is more powerful and long-lasting than doing so for a temporary pay-out. An example of this was the Game Makers for the 2012 Olympics in London — a community of people who just wanted to help. They were paid in free swag, social kudos, and an elevated status for their efforts.

Tapping into this source of expertise is not only possible, it also shows trust in the system.

Our recommendations:

At the very least, any source code from the app should be publicly accessible to allow for analysis by technical experts, privacy and security professionals. This code should be made public at least a few weeks before the launch date, ensuring there’s enough time to correctly interrogate it.

Any errors, security holes or backdoors that are highlighted need to be actioned as soon as possible – otherwise trust would be quickly eroded.

During the creation and delivery phase of the app, it’s important to work with the country’s top technical, privacy and security experts — whether from industry or research institutes — as their involvement will only increase the trust in the systems and the robustness of the output.

Privacy

You just need to look into the amount of focus that’s been on privacy concerns for the Track and Trace app, and potential misuse of tracing data, to understand how important this issue is.

Apple and Google’s project has attempted to balance privacy with the usefulness of tracking potential exposure. By design Apple and Google’s system does not track location, even if this location information could be useful to health officials. They both have brands they are trying to protect, so it comes as no surprise that they’ve leant towards a more privacy-focused solution.

Our recommendations:

Balancing privacy with usefulness will always be a tightrope to walk, but needs to be in line with the preferences and expectations of the community. Should more data be collected within the pandemic — which would be deleted afterwards — with clear m to be forgotten? Or should the data collected only ever be limited?

The correct decision is hard to define, except that any decision should be informed by the population. For example, Germany approached their app with very strict privacy guidelines from the start, which is very much in line with how the average German citizen feels about privacy.

Make it easy. For all.

Use what I’ve got

Sounds obvious, but making things easy for all is always a tough brief to execute. It’s important to spend the time upfront to make sure the barrier for entry is as low as possible. Outside of standard usability, best practices for this app is a key focus area to make sure the most at-risk users find the app as easy and accessible as possible. Other ways to increase ease of adoption is to break away from only thinking of it as an app, and work to use any existing infrastructures. Turn it from being just an app to being part of an integrated system or service.

Design for the most at risk

From early in the pandemic we’ve known that people over 60 are more at risk and make up most of the deaths. The current data show that 88% of total deaths come from this group, who make up 24% of the UK’s population — a large segment that includes 16.8 Million people. (The Lancet).

However, this demographic is the least technically literate of the whole population and less likely to own a smartphone – ownership is 70% for 55+ year-olds in 2020, compared with 95% for all younger age brackets. Put in absolute terms, this is at least 5 million people in a high-risk category who don’t access to a smartphone.

Our recommendations

It does not make sense that those who are the most at risk, and have the most to gain, are the most excluded from the app — they need to be put front and centre of the design process. Ideating around how to include and engage this segment might result in solutions similar to Singapore’s wearable tracking devices for the elderly.

Think system, not product

One way of making participation the easiest option is having it work seamlessly as part of a wider ecosystem — requiring minimal effort, or none, from users. It’s important there is a collective value for those participating.

Pubs and restaurants are an example where businesses (for the most part) are performing Track and Trace in a different way. The current tracing data collected is often done physically through paper slips, and is proprietary. This is fine, but the data is tied to one place rather than one person. From a user’s perspective this is a repetitive time-consuming task and only really useful if an outbreak occurs at that single location.

Our Recommendations

If the data was decentralised — held locally on peoples’ phones — a user would be able to enter the pub with a “COVID – health passport” that housed all their required information. This could be verified via a device, and a random ID assigned at the venue could be linked to the user in the event of a breakout. This could work with an ‘always-on’, device-agnostic solution which is better for those less technically proficient, or less likely to own a smartphone.

This could also be included as part of the booking process — for example, when making a booking via Open Table. As the user is making the reservation, we could propose a small additional step —as simple as a tick box for including ‘COVID – Health Passport’ code. Framed in the right way — ‘contributing to the health of fellow dinners’ — the user understands why this is required and is then motivated to act. From a business perspective, this can act as a badge of honour akin to a food hygiene rating.

Making the most of existing infrastructure and services

Rather than building new tools and features from the ground up, it makes sense to work with systems that are already built. This could be realised in a couple of ways:

Our recommendations

One option is to add Covid-19 relevant data into existing products and services, allowing people to be able to make better decisions. Imagine if Citymapper’s location data was used to map areas of high footfall, this information could then be surfaced contextually to help people make informed decisions based on risk. Before they decide to travel or book a meal out they might see: “At the time of your booking on Tuesday, Manchester Northern Quarter is busy”. Like a weather forecast, allowing people to plan ahead.

The second option is to make use of networks already in place. You can expect that adoption rates will be considerably lower for people who perceive themselves to be at a low risk of having a severe response when contracting the virus. However, it’s important they understand the impact their actions can have on other people, even without having downloaded the app.

Fortunately, these people have a 95% chance of having a smartphone and are more likely to be out and about — generating usage data with travel, e-commerce, booking or social products. If a restaurant has a confirmed breakout then, using live purchase data, you could imagine Monzo using it’s app to let people know they were present when an outbreak happened.

Or if you traveled through the underground station using your Oyster card, you could be notified that you’d recently traveled through a confirmed hotspot. This could even be pinpointed underground by the wifi-base stations you logged into.

When making use of other networks, it needs to be handled with due respect of people’s privacy. But there’s a wealth of data out there that could be repurposed to help the community, rather than just generating ad revenue.

A third, related point is to use the Oyster card network in London to allow people to tap-in and -out of locations, restaurants or events. The advantage is the technology already exists and is well proven. Oyster adoption is generally high within the population, including a reasonable percentage of the people at risk who don’t own a smart phone.

Ultimately, it’s about helping people help others

At first glance, the Track and Trace problem appears to have an obvious solution (or solutions) that didn’t exist in previous pandemics: our devices. We all carry them and they’re able to track our every move. While this may be true, a democratically-elected government is never going to able to fly in the face of privacy or civil liberties concerns and gain unfettered access to all of this data — regardless of how collectively useful this information might be.

This reality itself reinforces the reason why focusing on the behavioural change required to make this app a success is as important as the technical capabilities, if not more so. It requires us to look in detail at exactly who’s going to use the product, and why they might not be well suited or interested in the product.

So, our brief is to create an app that will help protect a large group of people who happen to be the least likely to be able to use said app, or have a smart phone. While at the same time engaging and mobilising another group who will not have any issues using it, yet will very likely feel it is unnecessary. What could possibly go wrong?

Because of these diverse groups and their different motivations, the strongest approach is to move beyond looking at the app in isolation, and see it as an important cog in a bigger tracing system. Leveraging existing infrastructure where possible will offer a greater chance of success because it’s removing adoption from being a barrier to success.

When you break down the problem of adoption, it’s actually no different from any other app. We need to convince different people what the benefits are to them, and why they should change their current behaviour.

But it’s precisely because Track and Trace is no different from any other app that we know we can overcome the various barriers, and we know it’s possible to build a product within the right system that can succeed in changing behaviour, and help save many lives.