Designing for Emotion

Establishing how we want people to feel as a consequence of using a product is a standard design practice. However, when someone is in a highly distressed state, it’s important to understand what frame of mind they are in when they arrive, in order to shift their frame of mind to a more positive state.

Here we share our Perspective on designing for emotion. We’ve gathered insights from our work in healthcare for organisations including BUPA, Boehringer Ingelheim and mPharma. With a focus on patients and people dealing with emotional circumstances, we’ll take you through the steps to build a framework for emotional design. You’ll also understand how this proven framework can be applied across other industries and types of businesses. We’ve used it to help businesses like Oakam Finance and Barnardos drive behaviour change by building a deep understanding of user emotions.

Connecting with patients saves lives

A recent Harvard School of Public Health study demonstrated that doctors who were more patient-centered and reassuring with their patients directly impacted the health of those patients. In other words, time spent emotionally connecting with patients actually saves lives. This points to the value that can be created by making that emotional connection through technology and the way healthcare services are delivered.

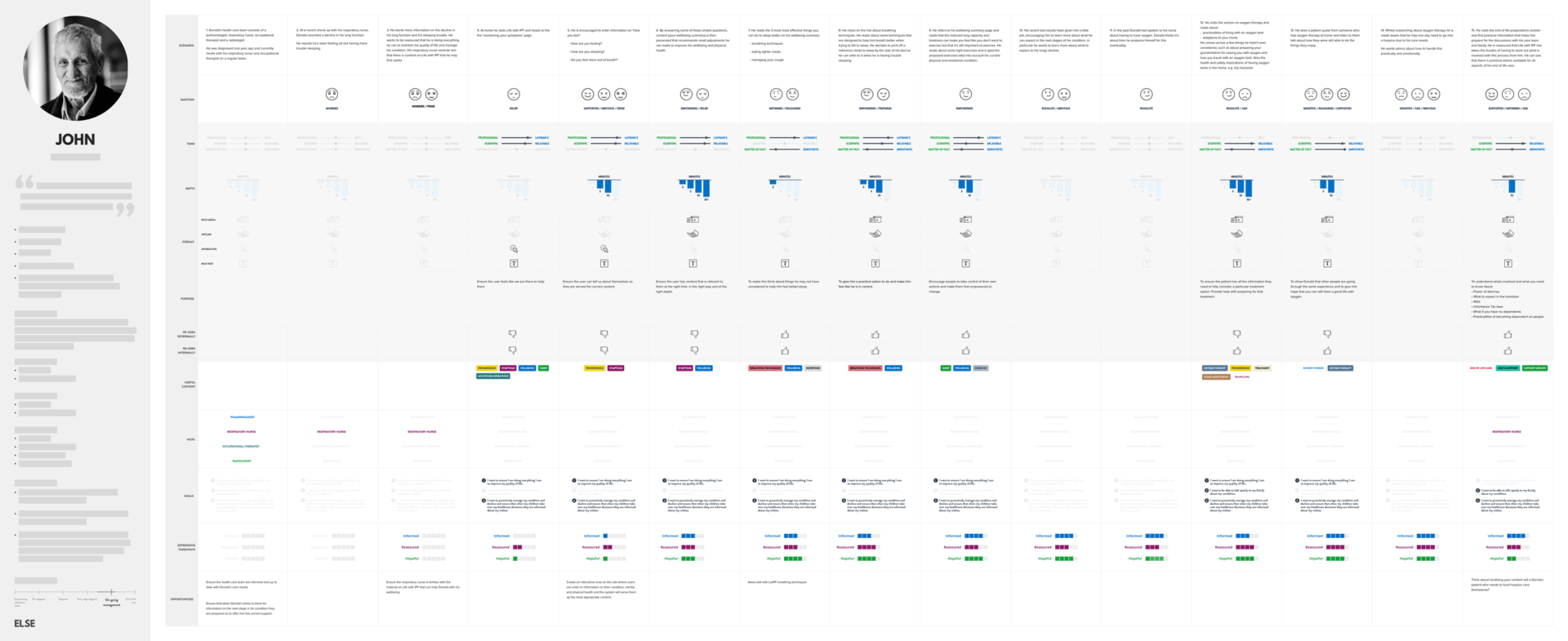

Designing across the patient journey

As it stands, design methods don’t take into account the emotional state users arrive in; mainly because it’s hard to understand and difficult to validate.

Instead there is an opportunity to leverage digital to design a service that’s much more targeted to a patient’s current needs. By understanding the different stages a patient experiences as they deal with a disease we can allow them to not only access the content they need now, but pre-empt what they may need next.

The difficulty increases when there are multiple emotional states to design for. Consider this: a medical support service for people dealing with a terminal condition. One patient has come to terms with their diagnosis and needs practical help with changing symptoms. Meanwhile another patient has just been diagnosed, is in a state of shock, feeling frightened, overwhelmed and needs help with understanding their condition.

What mechanisms do we put in place to create a nuanced experience for those patients?

The framework that sits behind an emotionally intelligent service should be capable of understanding the initial emotional state of its users and shifting them to a desired state.

To define the desired shift and the emotional response here at ELSE we create an Experience Framework. Our framework includes a set of principles which govern how the system should be designed and a set of Experience Takeaways that define how we want people to feel as a result of using the service. The product is designed in accordance with the Experience Principles ensuring that the final product will elicit the desired takeaway response.

We can use the framework as an input to ideation. It also becomes our measure as to whether experiences feel appropriate; taking subjectivity out of the equation.

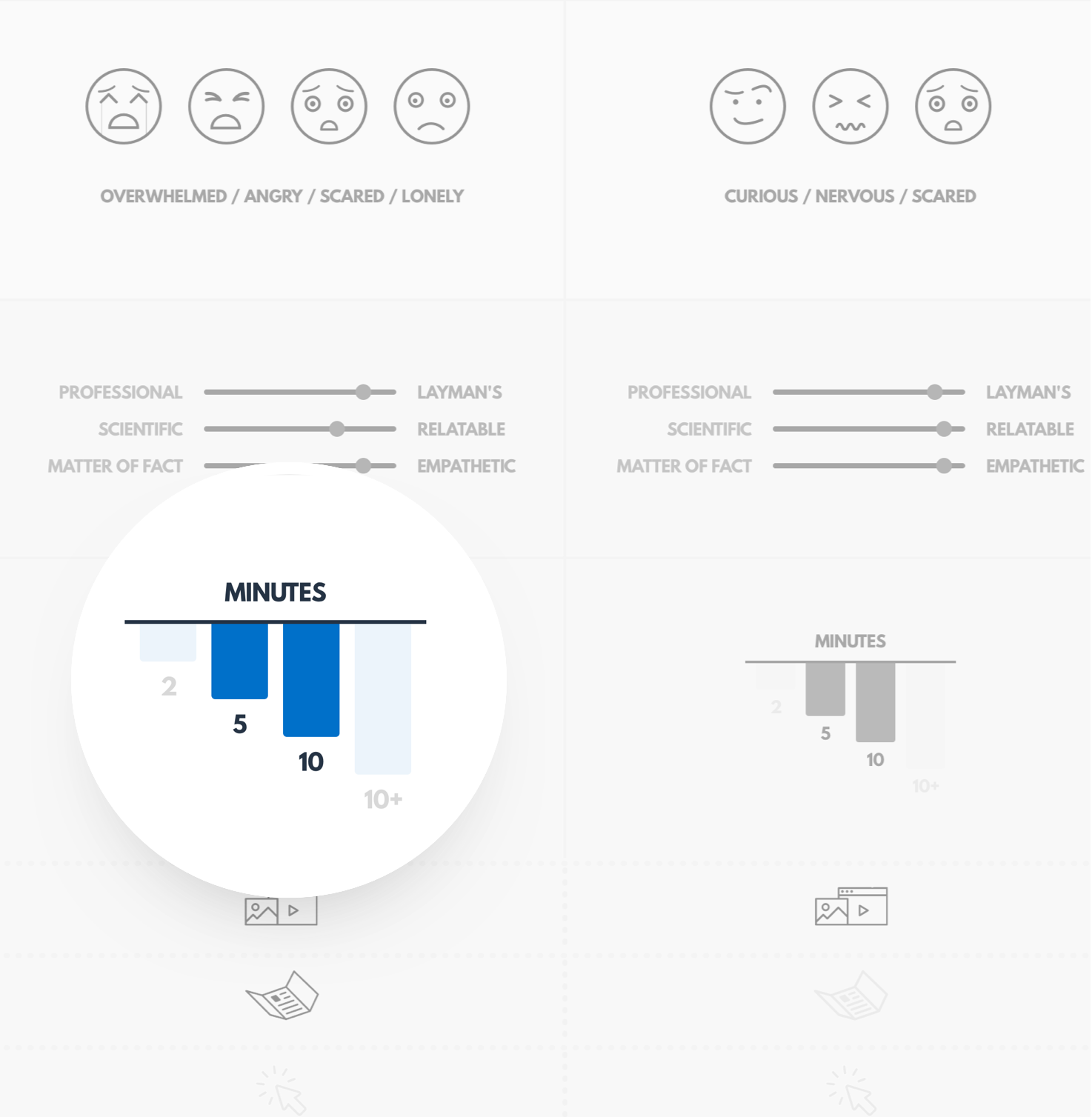

Understanding frame of mind

Emotion in

To truly understand a patients frame of mind it’s essential to understand their history and current circumstances.

Past experience & personal circumstances

- how long it took to be diagnosed

- how they received their diagnosis

- how they were treated immediately after

- their understanding of the condition

- and if they have a personal support network.

For example, someone who has spent four years undergoing tests and doctors appointments may feel a sense of relief when they are finally diagnosed but conversely could also feel let down by their GP and may feel a sense of frustration or anger.

Once a patient’s history and personal circumstances are understood, we then need to consider their character and personality. Personality plays a big part in how the user responds and acts upon the information they are given.

The past experiences of patients leading up to diagnosis have a huge bearing on their emotional state and their outlook. There are many factors which have an impact on a patient’s emotional state, including:

Personality and the patient experience

Personality is the most difficult factor to deal with because of the way it can impact the patient’s response to the information they are given. Two patients in a similar circumstance with similar needs, may have a completely different outlook on their situation. The personality factors that impact most on the goals of the product need to be identified in order to engage with them on their terms. At a basic level, understanding if someone is proactive or reactive gives us different content opportunities.

Proactive and reactive personalities

In occupational psychology, it is suggested that those with a proactive personality are more likely to control their situation rather than just respond to it. They have a disposition towards taking intentional action to influence their situation and environment. Whereas people with a reactive mindset would generally allow others to control their situation and respond to events after they have happened.

Even though these personality traits are not binary it’s important to design for them as if they are. Carefully considered personas with opposing personalities allow us to cater to both the extremes and all those in between.

Introverted

“I need someone to help me make sense of what is happening to me.“

— Raymond

Determined

“I am at ease with my condition, I want to remain in control of my healthcare for as long as I can.”

— Edward

Creating a framework

Measuring every interaction

Emotions are shaped during each interaction with the service, ensuring our patient journeys are created for each persona to establish where the experiential opportunities exist across that life cycle.

With a terminal illness, there are specific physical states that a patient will encounter pre-diagnosis, diagnosis, during condition management and end-of-life. In addition to the physical states, there is also a progression through a series of emotional stages. The Kübler-Ross model describes a series of emotions that someone who is grieving may experience. They are; denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance, symptoms and treatment. Progression through the Kubler-Ross grief model is not necessarily linear and it’s possible that not every state is experienced.

By using the physical stages of a terminal illness, in addition to these emotional stages, we can then create a framework for the patient journey which can be applied to each set of circumstances, needs and goals.

Personas and empathetic understanding

Populating the framework and plotting how a patient feels during each stage of their condition helps us to ensure their needs are met. To do this a scenario for each persona is created and against each step, the feelings of the persona are plotted. It is essential that the design team has a solid empathetic understanding of the different personas, their background and their personality because at each point in the scenario the team has to step into their shoes to consider their emotions, feelings and frame of mind. Working through this can therefore be an emotionally taxing process.

Shifting the emotions

Emotion out

Anticipating the emotional state of the patient when they first encounter the service is only the first step. What we want them to feel as a consequence of using the service is involved and can only be done by ensuring the right framework, functionality and content is served at the right time, place and altitude.

Using the mapped out scenarios and the understanding of the personas’ emotional state at each point, enables us to orchestrate how content should be presented at each point, what tools may be needed and what rules need to be applied in the system – across the patient experience.

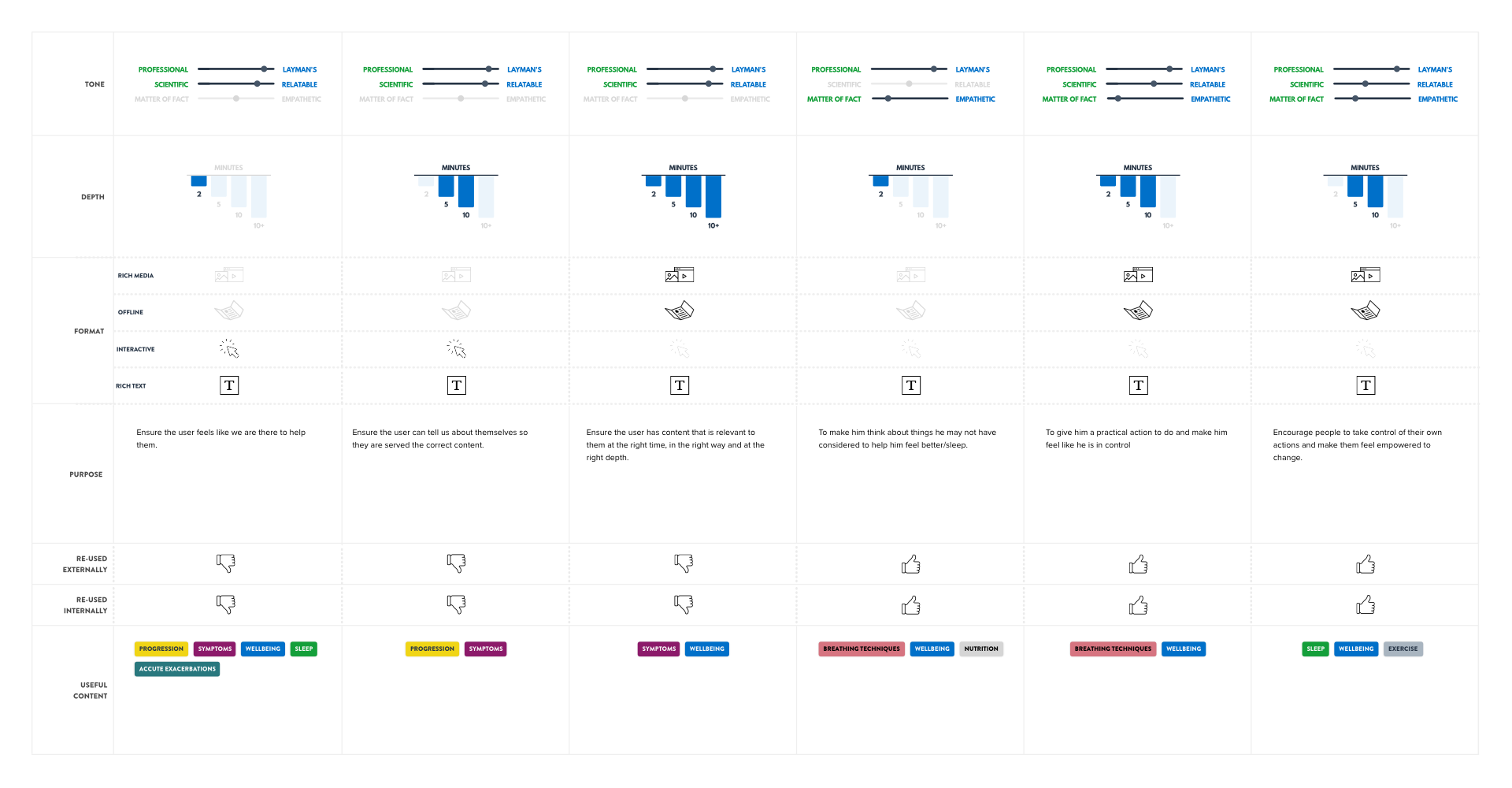

Setting the right tone

The content needs to encourage patients to take control of their condition. To do this it’s important for patients to:

- truly understand the information that’s presented to them and

- know exactly what they can do next to manage and take control of their condition.

For that reason, content should be considered in terms of tone and also how detailed it is.

When the subject matter is so sensitive getting the tone right is important. Sometimes different topics may require a shift in tone to truly resonate with the patient.

Consider patients that need at-home support, for example. That may be in the form of a connected companion service in the home, or a family member taking on the role of carer. Knowing emotions in/emotions out will help ensure content, tools and advice can be served up to help people to help them manage their own condition, or care for others (e.g. exercise routines, advice based on patient feelings and what to do about it).

Content written in a professional manner, using clinical terms and a higher level of language can alienate a non-practitioner audience. Whereas content written in lay terms, keeping the language simple and using examples to aid understanding can have a much bigger impact and resonate better with patients.

Serving content with the right level of detail

Patients consume content at their own pace depending on where they are with their acceptance around their diagnosis. For this reason content should be tailored to different scenarios, offering flexibility to patients. For example the level of detail should be different between those who may want to understand the basics of their condition and those who may want a detailed explanation. To provide the right level of information, the content should be progressively revealed, enabling the patient to choose the pace of consumption.

Considered imagery placement

The use of imagery also needs consideration, particularly when relating to the stark reality of a condition. Imagery showing how symptoms can manifest may provide relief to some making them feel that they are not alone, whilst that same image may be intimidating to others who haven’t yet and may never will reach that severity in their symptoms. By identifying where and when such images appear ensures only those ready and willing to view these will do so.

When working on services for rare conditions, some of the symptoms can include visual disfigurement. It’s important to ensure this development isn’t visibly shown at a point where people are coming to terms with their diagnosis.

Creating the right functionality

Whist the manner in which the content is written is incredibly important, so is the functionality that supports the understanding of that content. For this reason functions such as bookmarking, highlighted tips, interactive glossary terms and downloadable resources can be designed into the service to support the patients understanding.

Creating the right rules

When designing a service for distress there needs to be a set of rules which holds the service together, to ensure the Experience Principles are fulfilled. If the service that is being created is to be rolled out across different territories then it is these rules that will ensure that the Experience Takeaways are still fulfilled.

Ensuring the Experience Takeaways are fulfilled

By monitoring patients’ emotional states throughout the experience we can check if they are inline with the desired Experience Takeaways we have set in place. It is unrealistic to expect to fulfil on each takeaway at every point in the journey and we should allow ourselves to adjust them based on their fulfilment. By having the content, functionality and rules in place it means we can be confident we are shifting the emotions in the right direction as the patients interact with the service.

Early testing and validation

Finally, every system needs to be tested and validated before and after launch. Validating the framework requires early testing on the patient journeys, whilst post launch the service can be validated by a wider audience by designing into the system opportunities for the patients to feedback on the product. Using this feedback the service can be incrementally fine tuned to ensure continual improvements happen over time.

A framework made up of four dimensions

1. Define the end-to-end patient journey

Investing time in understanding the end audience and clearly mapping out each key stage in their journey lays the foundation for the emotional design framework. We should look at this as a set of steps they take and describe the actors in play — are they arriving in isolation, as a carer, or in conversation with their clinician? What do we expect them to do, what is their scenario? What is their onward journey?

2. Set the right tone in the content and tools

By understanding the context of use, we can use the appropriate tone at the appropriate time. This means that rather than have a single tone-of-voice, we can flex it to suit the situation and be more appropriate. This applies also to delivering the right tools to aid comprehension and enable people to action that information.

3. Apply the 2, 5, 10 rule to content depth

Allow users to “Skim, Swim or Deep Dive” by sharing content in length and formats suited to 2-minutes, 5-minutes and 10-minutes. This flexibility offers people the opportunity to go as lightly, or deeply, as they please and it affords us the opportunity to guide the pace of immersion in that content.

4. Measure the shift

By defining a set of experience takeaways, we can question whether we are delivering the desired outcomes for each person, at their desired moment in time. We can use each takeaway as a lever, so the experience has a rhythm to it and we can demonstrate how we’ve taken an existing feeling and amplified it for that person’s context.