An R&D Perspective

AI and the future of education

Foreword

At Else we dedicate one day in ten to R&D. It’s precious space for our teams to self-initiate curiosity-driven research projects. Back in 2018, when AI excited only a niche few and ChatGPT was still years from launch, we conceived a vision for education in 2049. In most cases, the ideas you’ll find here are fast becoming a reality right now, 25 years ahead of schedule…

Back then, we discussed many possible themes, yet there was always a recurring point of convergence in our conversations: How artificial intelligence will have a leading role to play in our future.

So having put a pin on AI we needed to find an angle that would allow us to frame our exploration and thinking. We talked about the future state of work, politics, the environment… but education seemed to be the space that sparked something in all of us.

So we finally set out to explore: AI and the future of education.

What’s more evident today than ever before is that learning is not a linear process – it can happen anytime, anywhere. Yet the traditional education model is typically rigid, calling for children to learn in a specific way, in a specific place and assess their knowledge at specific times.

Through this R&D project, we take a look at how AI has the potential to radically change the landscape of education. From drivers and catalysts of change, to hyper-personalised curriculums, real-time holistic evaluations, and AI teaching assistants – let’s step into the classroom of the future.

N.B. As this is an ongoing piece of (unscientific) work, it contains some non-sequiturs and blind alleys, but that’s the fun of research. We hope you enjoy reading about it as much as we enjoyed doing it.

This article is in two parts:

- Setting the context: The road to future learning

- A vision: Future of education

The road to future learning

Drivers of change

The western education model has come into a lot of scrutiny lately and there are several signs showing that it is a system reaching a tipping point.

We hear about schools having a recruitment crisis, about shrinking catchment areas and slipping school standards. We also hear about a widening educational gap between the advantaged and the disadvantaged – with data suggesting the latter being on average a year and a half behind their richer peers in the UK.

If we look at the situation globally, the inequality is even greater.

Abigail Cox in her article on EdSurge Independent says:

“The educational system was built with a bias; bias in deciding where to direct funds, bias in the material we teach, and bias in where the school is located. It makes all the difference in the world if your neighbourhood is wealthy or poor. The bias is dependent upon “the have and have nots” mentality, and this bias determines student success.”

Limited access to good teachers, quality provisions and opportunities is what we considered being the first driver of change.

Schools have also been criticised for not preparing young people for the world of work effectively. A survey conducted in 2015 by the British Chambers of Commerce shows that most business leaders believe that young adults are ill-prepared to get on the career ladder, lacking fundamental skills.

The main reason behind this is the fact that the national curriculum has always been behind the curve of the demands of the job market and does very little to prepare young adults for tomorrow’s job world.

In desperate need of modernisation, an outdated curriculum was therefore what we considered being the second driver of change.

Finally, the current exam-based methodology of assessing comprehension and mastery of a certain body of knowledge can never be truly representative of one’s ability.

Some people just test well, while others don’t. One day you might get lucky in an exam – and get the topics you studied – and the other day not. But more importantly, exams and the qualifications associated with them, don’t provide the full picture. They are only representative of one’s performance on a given day — like fixed keyframes in a timeline.

So the third area we thought needed transformation was the current ineffective assessment method.

Catalysts of change

The next exercise we went through to help us paint the picture of a possible future, was to speculate how technology and mindsets – we thought were relevant to this field – would evolve in the next 20 years.

To help us do that, we first looked at how today’s technology was inspired by yesterday’s fiction and then we time-reversed the process to see how current nascent and even fictional tech could evolve, mature and eventually fall into mainstream in the future.

The technological roadmap (present to future)

1. Artificial Intelligence

Since the conception of the term in 1950, it has taken AI eight decades to have a noticeable impact in our daily lives. NLP voice assistants, intelligent recommendation engines, and self-driving cars were all once science fiction.

Today the use of some of these applications has become so mainstream, that some would say it’s even verging on the banal. But while current AI applications provide certain utility, they don’t yet allow us to seamlessly mix our cognitive and analytical capabilities with that of machines.

Our vision for the future of education was for people to be able to use AI as a means to enhance inner discourse and to do that, technology needs to develop much further.

Here is how the field of AI could evolve:

In 2025, Google releases Live View – an AI building block that recognises objects, places and actions in real-time video streams and camera feeds. Facebook follows soon after with their own proprietary version.

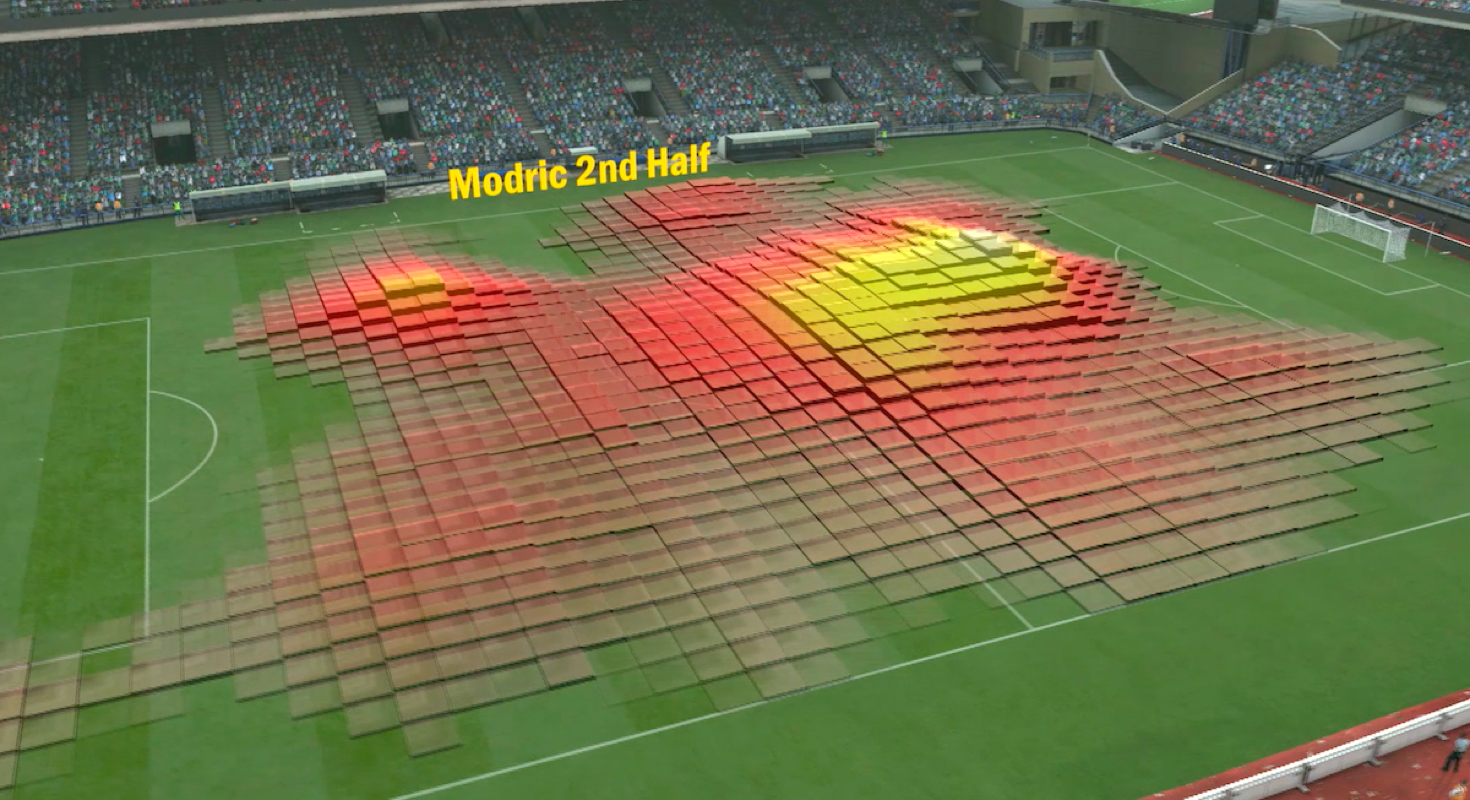

Next, Amazon acquires the Piero sports graphic system from Ross Video and two years later, it offers its capabilities to Prime Video subscribers for personalised use in their live sports streams.

Originally developed by the BBC, the Piero Sports Graphic system is a 3d tool that helped analyse and explain sports events

Originally developed by the BBC, the Piero Sports Graphic system is a 3d tool that helped analyse and explain sports events

Next Amazon collaborates with Open AI to develop alternative uses for Piero and they co-launch the first multi-purpose real-time graphic system. It enables augmented reality developers to create applications that allow users to observe and analyse situations in physical environments.

Later, in an effort to accelerate the development of artificial general intelligence (AGI), some AI companies join forces and agree to release free versions of their software to the open-source community for study and experimentation.

Two years later, a global team of academics comes a step closer to emulating AGI, by cobbling together the very first platform that allows AI capabilities from different providers to be stacked together and work in unison — They call it Athena.

In order to maximise data access and accelerate machine learning scope, project Athena continued development with a focus on backwards compatibility with legacy devices.

Finally, while not be most feature packed solution, Athena is the most accessible and widely used system owning 48.11% of the global market.

Augmented reality technology with multi purpose graphic systems allows users to interpret the observable reality. Even though the technology has been really useful, at times it has also been criticised for reinforcing confirmation bias.

2. Augmented, Virtual & Mixed Reality

During the two decades preceding 2050 we are seeing huge leaps in terms of technological development in the augmented, virtual and mixed reality space.

At the higher end, Google, Microsoft, Apple, HTC and Amazon Valve are still sharing the biggest portion of the pie but there are now tens of other independent companies that offer alternative and more accessible solutions in the hardware market.

The average entry-level price of hardware has lowered to the point where the technology becomes as ubiquitous as smartphones are today.

In the early 30s, the proliferation of reality devices prompted the W3C to create a new ontology language extending their semantic web technology stack to the physical world — World Ontology Language (OWL)

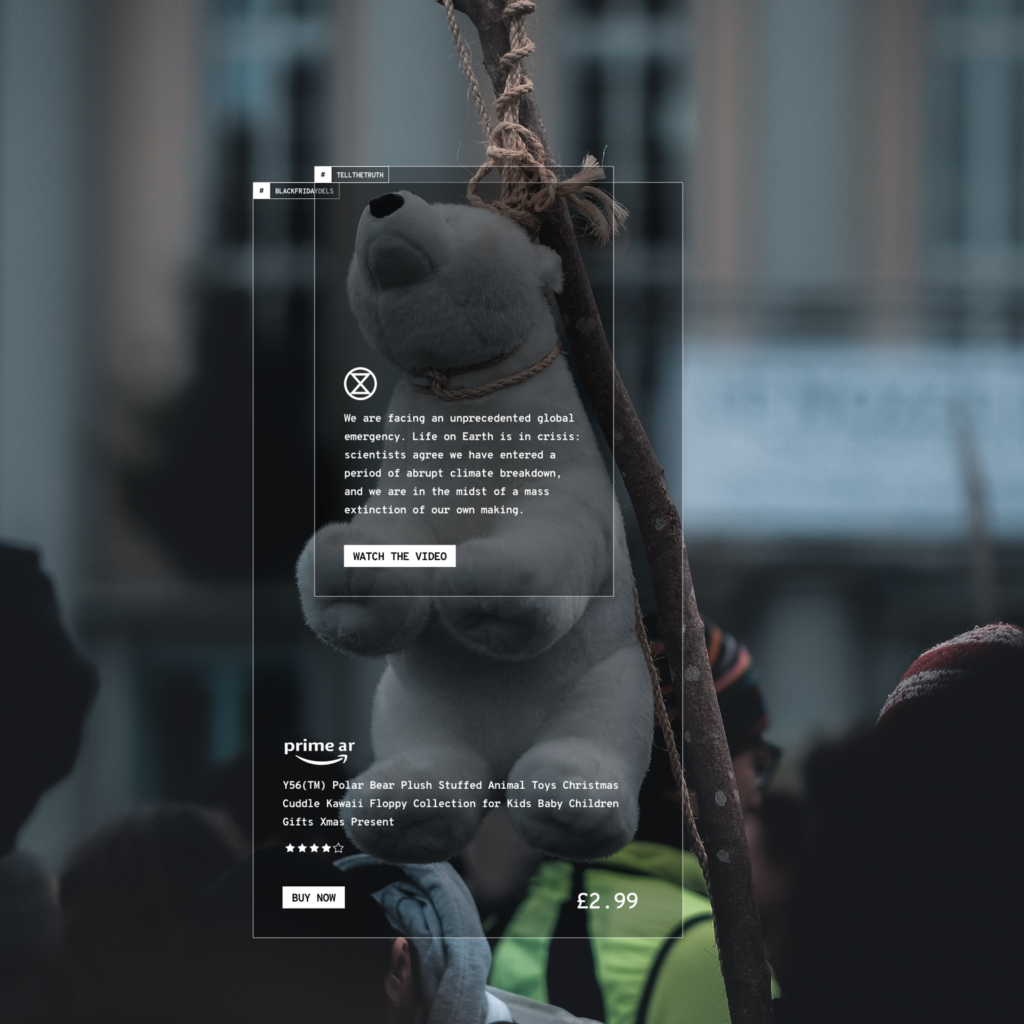

The ultimate goal was to make real-world objects more accessible to programs. This innovation becomes the catalyst for the birth of a new trend — object-tagging.

Artists are the first to experiment with object-tagging but it doesn’t take long for adoption to explode. Businesses, marketers, academics and influencers enter the race and reality is rapidly becoming saturated with digital noise.

At the end of the decade, Google, Microsoft and Athena launch a new type of A.R browser that allows users to filter digital content in the physical world based on their preferences, behaviour, affiliations, and social relationships.

Accessing augmented reality information becomes as easy as asking Google a question or Alexa to play a song.

Evolving mindsets

1. Alternative education models

The limitations of the western educational model became increasingly pronounced as the world population grew steadily.

Over the three decades preceding the half century mark, increasing demand on formal classroom teaching reached a point where it was no longer serviceable.

As a consequence, alternative education models like home schooling saw a dramatic rise in popularity and new models arose like sponsored learning and Sit(uated)-Net(worked) learning – forms of AI assisted education that were both officially accepted by governing bodies and employers alike.

2. The post-classroom era

With ever increasing classroom sizes and teacher-to-pupil ratios plummeting well below the recommended guidelines, teachers worked progressively harder while results declined.

As a result, private tuition demand saw a big rise in the late 20’s with the market reaching an estimated value of 3bn.

But the private tuition model had a scalability limitation for tutors that kept session prices high, which in turn translated into an affordability problem for households.

With prices ranging between £20 to £70 an hour for a single session, those who could afford private tuition, had to find the right compromise between price, quality and frequency.

To illustrate the point, let’s take two families from a similar socio-economic background: the Smiths and the Sergeants.

Both families have a need for their children to complement their education with private tutoring and have a fixed available budget of £70 a week. Ben Smith, needs some help with maths, while Alexia Sergeant needs help with both maths and physics. That means that while Ben’s parents can choose their preferred local maths tutor who charges £70 an hour, Alexia’s parents have to either compromise, or prioritise.

In the mid 20’s, inspired by platforms like Masterclass and Peloton, Amazon introduced a new AI-enabled service that promised to deliver the benefits of one-to-one tuition for learners, while ensuring maximum reach for teachers.

By using Alexa as the underlying technology, teachers could create their unique voice assistant profiles, trained to simulate their personality, tone, voice and teaching patterns.

That meant that if a user had a profile installed, s/he could always access personal teaching assistance without the need for a teacher to actually be online.

By removing the one learner per session limitation, the Amazon Education Network provided the first marketplace that enabled teachers to reach a global audience.

And with the scalability problem solved, private tutoring became accessible to households of all income brackets.

Historic interactions with personal AI assistants could reveal much more complex aspects of one’s personality

3. The new quantified self

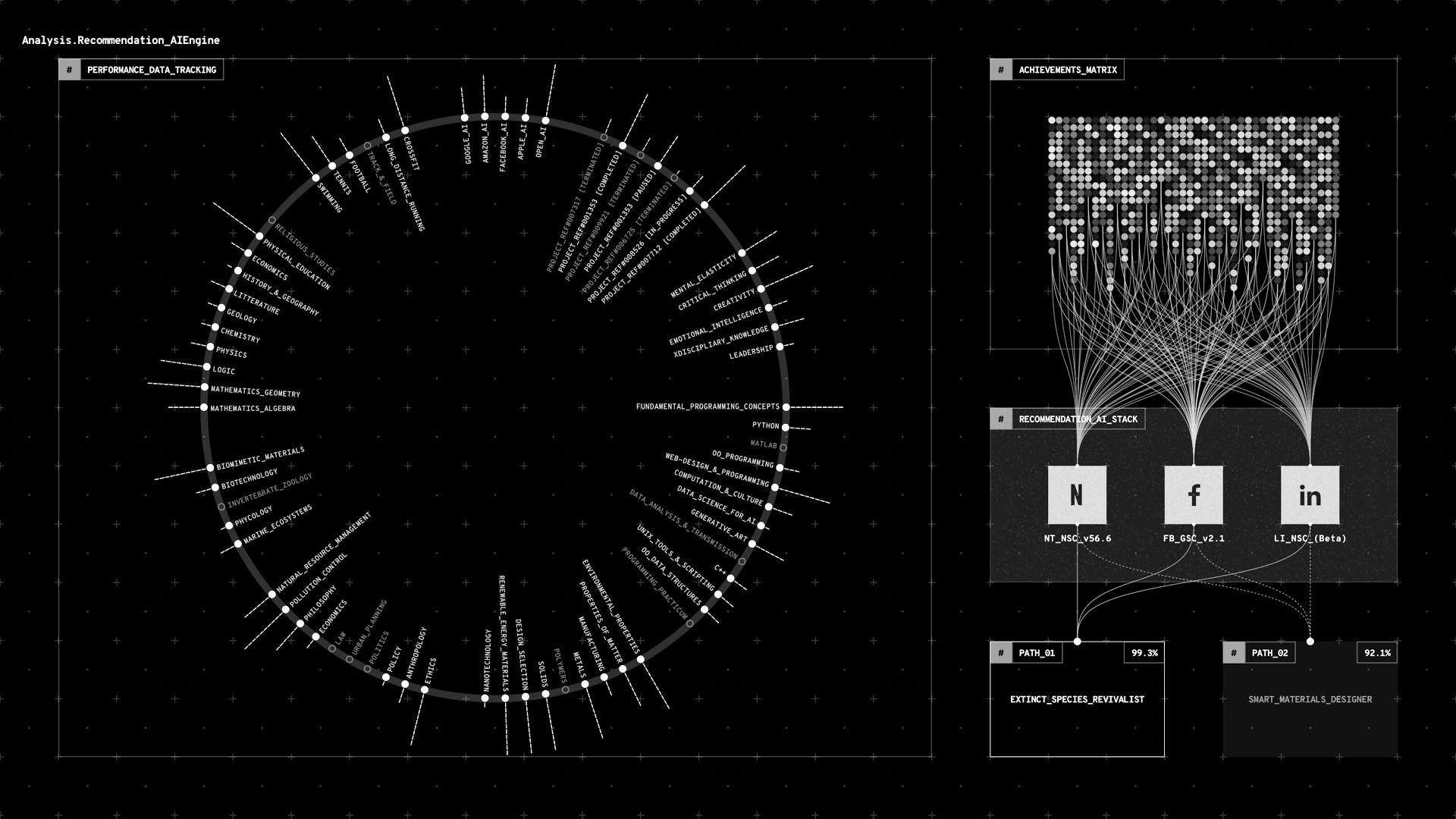

While AI helped people to observe and analyse the outside world in new ways, it also provided an esoteric porthole that allowed them to better understand themselves and others.

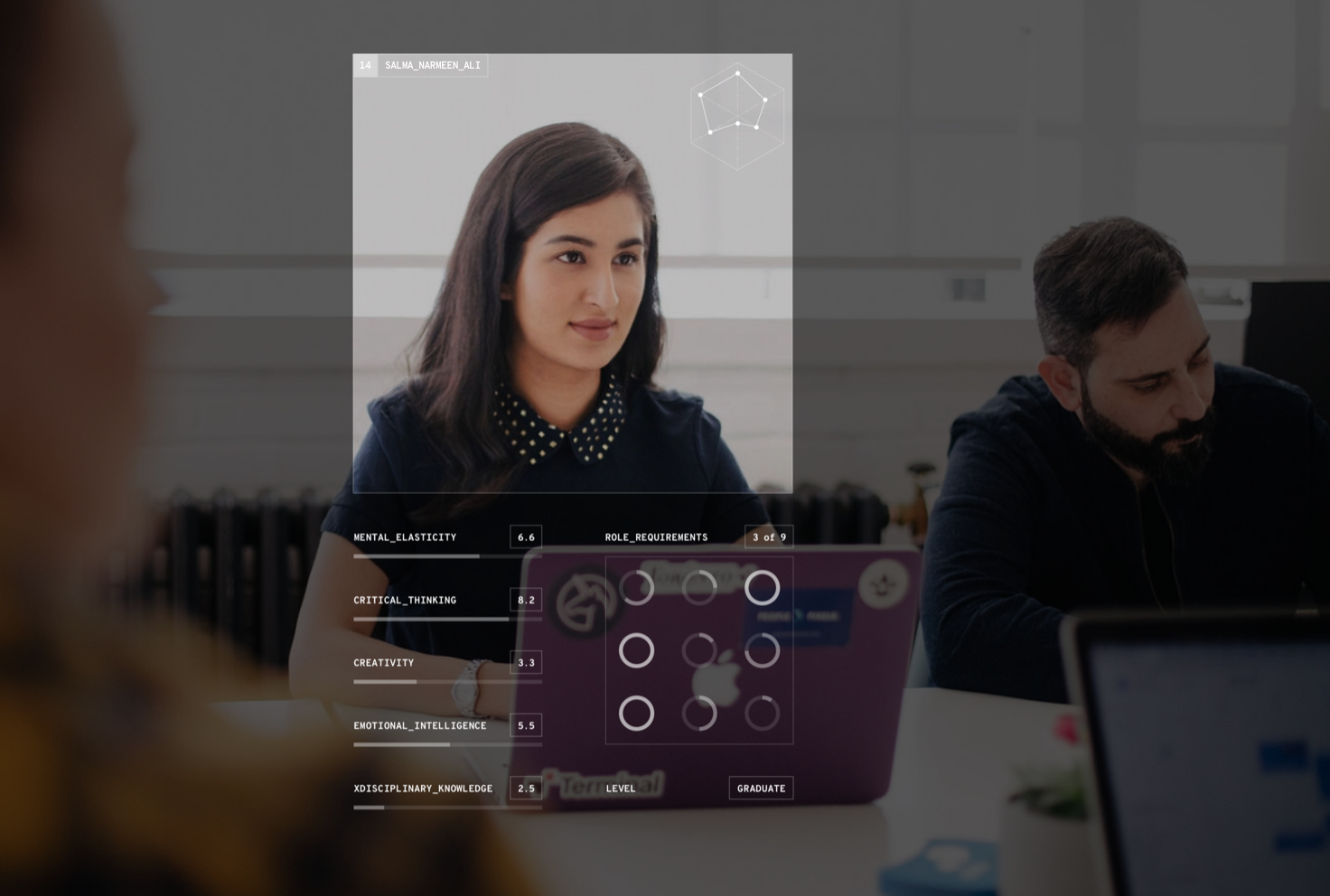

In the same way that one’s browsing history can tell you a lot about a person, historic interactions with AI assistants could reveal much more complex aspects of one’s personality — like sensitivities, biases and mindset.

But more importantly, by looking at how one acted as a consequence of their interactions with AI, the technology itself could extrapolate and quantify previously intangible attributes like creativity, emotional intelligence, mental elasticity and critical thinking.

This was a game changer for employers as it allowed them to have more insightful qualification criteria for candidates besides academic achievements.

4. Hyper-personal learning

Last but not least, the most notable paradigm shift in education was the evolution of the definition, structure and delivery of the curriculum.

Learners were no longer restricted neither by a single delivery method nor by a designated linear process. So in order to learn, it was no longer needed to attend a specific classroom at a specific time taught by a specific teacher in a very specific way.

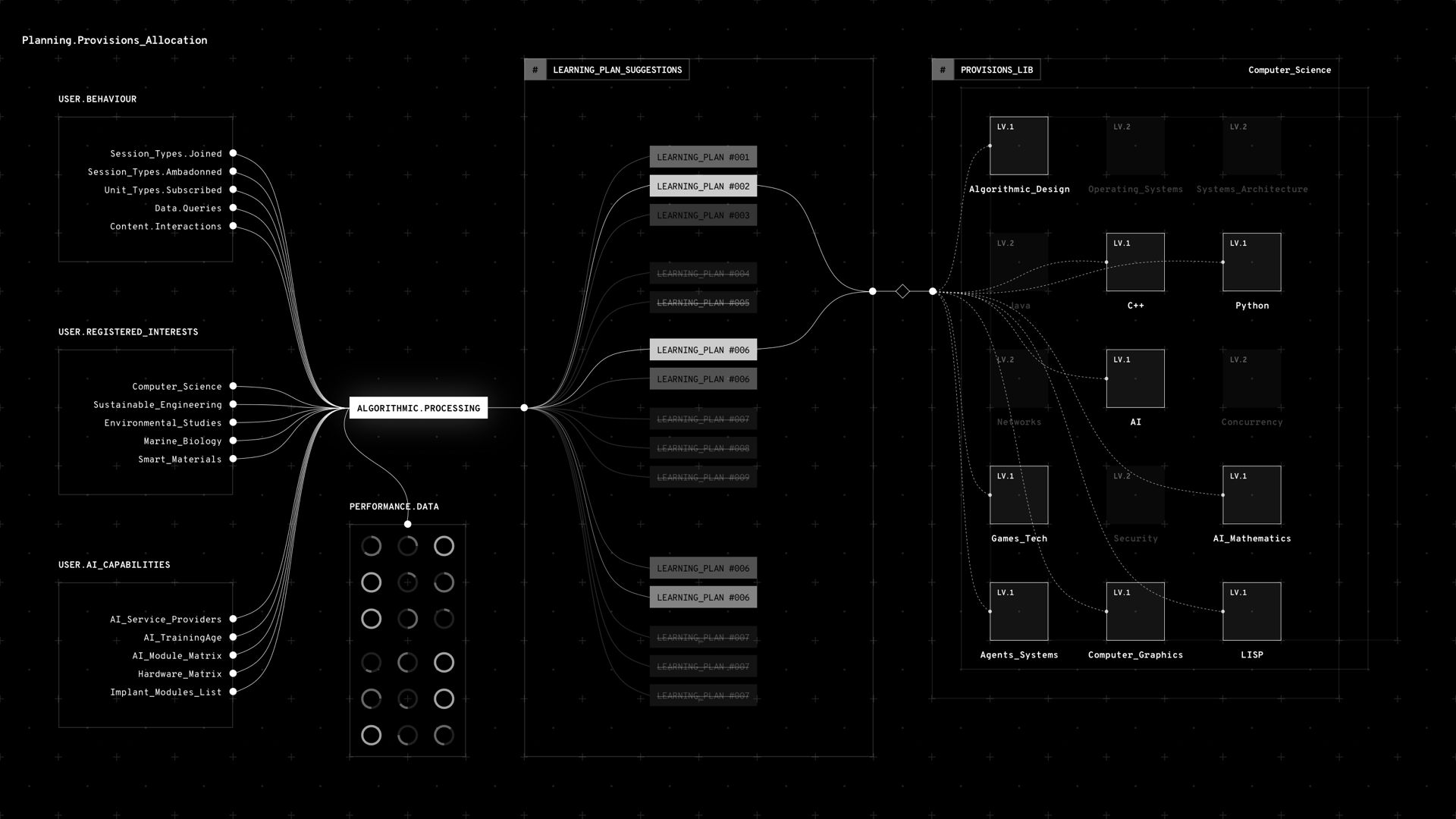

Personal AI would adapt to the needs, stimuli, learning patterns and preferences of the learner and suggest optimised learning plans with dynamic lesson provisions that could be accessed at any teachable moment.

One could learn aspects of trigonometry while playing football or concepts of political science while watching Homeland. Every moment had the potential to be a teachable moment and every context could be turned into a situational learning playground.

The only thing you needed to be was curious.

This lead to an overhaul of the assessment system and instead of evaluating knowledge periodically at fixed moments in time (through exams), learners would be evaluated continuously in real-time through their queries, interactions and learning progress.

Structured courses didn’t disappear entirely though. But rather than being a set compulsory modules that one could either pass or fail, they were used as classes in the back-end to provide lesson provisions and pathway recommendations.

As a result, professional orientation instead of being associated loosely to degree types, would be algorithmically calculated by actual knowledge and skills acquired and mastered.

Atomised learning data is used by an AI engine to recommend professional pathways that best fit the capabilities of the learner

The future of education

A teacher’s perspective

Having speculated what a possible future landscape could look like, the next step was to take a stab at loosely illustrating the user experience for our two core user groups: Teachers & Learners

For teachers, we wanted to explore a synergistic relationship between technology and people, and more specifically look into the areas where AI could augment human capability.

Having interviewed several teachers at different levels, we found out that while they love teaching, some aspects of the job were consuming a lot of time and effort, resulting in a negative experience.

These pain points provided us with the key opportunity areas where AI could step in and take the load off teachers and allow them to focus on doing what they loved: Teaching.

Planning

There were two forms of planning that we looked into. One was planning curriculum and provisions for the day, term and academic year and the other was what is known as “In The Moment Planning’ (ITMP)— a method used specifically in the Early Years Foundation Stage.

In the moment planning is a very simple idea – observing and interacting with children as they pursue their own interests and also assessing and moving the learning on in that moment. The written account of some of these interactions becomes a learning journey

Early Years Foundation Stage Forum

Theoretically, ITMP is a more effective teaching method because by constantly taking into account context and adapting the lesson to the current moment, it ensures that the imparted knowledge is directly applicable and coherent.

But the concept also has critics – the pragmatists.

This is what an Early Years Foundation stage teacher and ITMP advocate told us in an interview: ‘It takes a lot of hard work and good knowledge of the children… many in EYFS don’t think it works because you need to be really on it.’

This is where we think personal AI teaching assistants could step in to address the issue. Instead of relying on a teacher’s ability and capacity to observe and adapt lessons, personal AI could do that for every learner in real-time.

Since personal AI is aware of the user’s current activity, it can therefore adapt the lesson, choose the most effective provisions, look at outcomes and

Observing

Observation is another important part of a teacher’s job, but it is also one that is prone to failures – especially when the group is beyond a certain size or when teaching happens remotely.

Due to the fact that a teacher’s attention is limited, teachable moments can be missed, and certain group members can be underserved.

But with a network constantly analysing learners’ data and relationships, teachers could potentially evaluate both group and individual situations more effectively and choose in which situations they need to intervene.

For example teachers could be asking the system questions such as:

“Athena…

-

- show me who has had the most interactions”

-

- show me the who has the strongest connections”

-

- show me which learners are isolated” – etc…

Of course these questions can also be answered today – whether it’s in a real classroom environment through observations and notes, or in a virtual teaching platform through analytics and video feedback. But current systems have long lags between brief, execution and feedback. In the future the difference will be in the time it takes to capture and process that information. Future technology would make that process instant and remote teaching more effective.

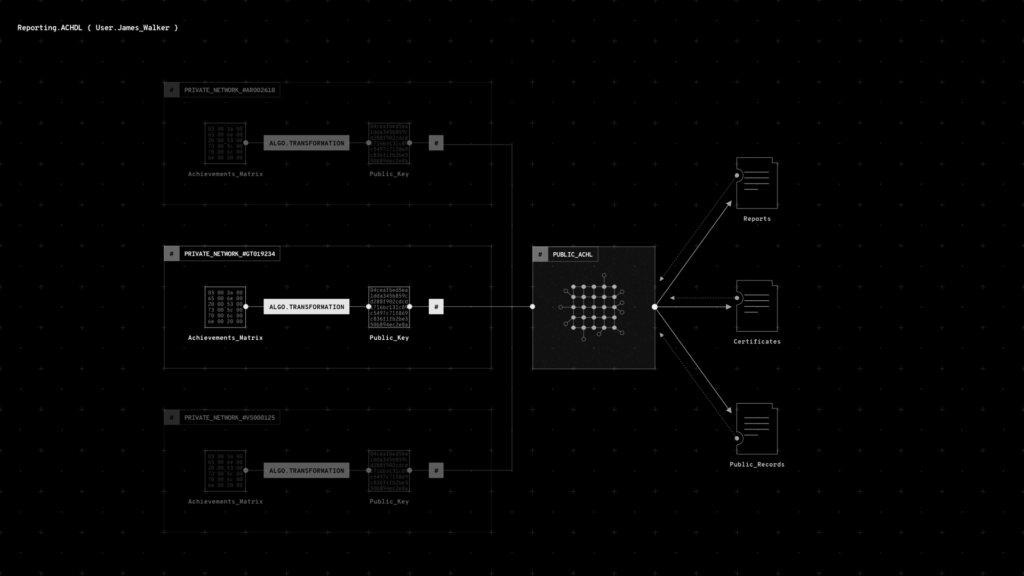

Reporting

Creating reports is another time-consuming process that is in desperate need of modernisation. Teachers have to go through multiple records – analog and digital, synthesise and generate reports for different purposes.

Here is a list of some types of reports that teachers need to generate at a regular basis:

-

- Parent reports

-

- Special needs funding request for the local authority

-

- Vulnerable children case studies

-

- Results and performance reports

-

- School archives

-

- Discipline specific reports

-

- Moderation reports

-

- Baseline assessment reports

-

- Ofsted evidence data

What usually happens in the above scenarios, is that teachers will be looking at archived information, extract what they need, repurpose it to generate reports for different purposes and then distribute it to the relevant parties.

A smart archival system could turn this repetitive manual overhead obsolete by allowing an automated generation of reports. The system would handle query requests depending on permissions so the only responsibility for teachers would be to maintain data integrity.

Below is an illustration of how a distributed hybrid smart ledger could be used to store learner data in a private network while allowing different parties to access data permissible to them in a public network.

A restricted access public network hosts a learner’s records aggregated from several private networks (schools). Data can be shared externally with parties that have the right permissions (keys)

A snapshot from the future

So from a teacher’s perspective, what would an AI-enabled virtual classroom look like? Here is a short video we put together showing ATHENA’s core features:

Well, there you have it folks, that’s how far we got to in the short amount we had to bring this idea to life. Going forward, we would love to explore what a learner’s point-of view would be as well as the potential dangers of this technology as we know that there is always a dark side to technology that as designers we need to be mindful of. But that’s for another Friday.

To be continued…