Human-centred design

Designing for human interactions

Design is the creation of a blueprint for human interactions with objects, processes, systems, or software.

A process centred on meeting human needs, design requires consideration of the numerous factors that will affect a person’s perception, interaction and engagement with the world.

Mental models

Complex creatures operating in a complex world, with a finite set of resources to complete complex tasks, people use a variety of techniques to help them simplify their decision-making:

Heuristics: Rather than understand all the details of a situation, people make decisions using approximate rules of thumb.

Framing: Rather than evaluate each case on its individual merits, people often rely upon anecdotes or stereotypes as emotional filters to understand and respond to events.

Cognitive biases: There are a number of biases in the way we think, possibly as a result of evolutionary pressure – for example, loss aversion might have arisen in the context of subsistence farming, where losses can carry a very high price.

By understanding the psychological underpinnings of human behaviour, we can help people achieve better ends, by designing experiences that rely upon these insights, alongside the traditional levers of incentives and information.

Changing behaviours

When approaching any design-led activity consideration must be given to the aesthetic, functional, economic, environmental and socio-political dimensions of the design object, and how the object designed provokes a personal response on each of these dimensions.

As a company that designs experiences, at ELSE we consider each of these aspects when helping organisations design experiences for their customers.

And as we are particularly focussed on those aspects that help organisations change their customers’ behaviours.

These can range simple changes like making them more likely to press a button, or complete a simple task, to massively more complex long-term customer engagements like living a more healthy lifestyle, or planning for their financial future.

A simplistic approach to changing behaviour might simply rely upon a mix of information, instruction and incentives – provide people with all the detail they need, tell them what to do, and give a reward for making the right decision, and they’re bound to do what you want.

But that is to misunderstand what humans actually feel, think and do.

To help people change their behaviour, you have first to understand how they behave – which sounds simple, but isn’t, because people aren’t simple, and they don’t behave in a simple fashion.

Mindspace

One of the most effective models we’ve encountered for mapping the decision-making landscape is MINDSPACE, developed by the UK Government to help people develop policies, design and practices that take account of how people think when asking them to make decisions and change behaviours.

MINDSPACE is a mnemonic checklist of the influences on human behaviour which help us shape the design of experiences we create for our clients’ customers, by understanding how these customers think, and designing the experience accordingly (i.e. human-centred design).

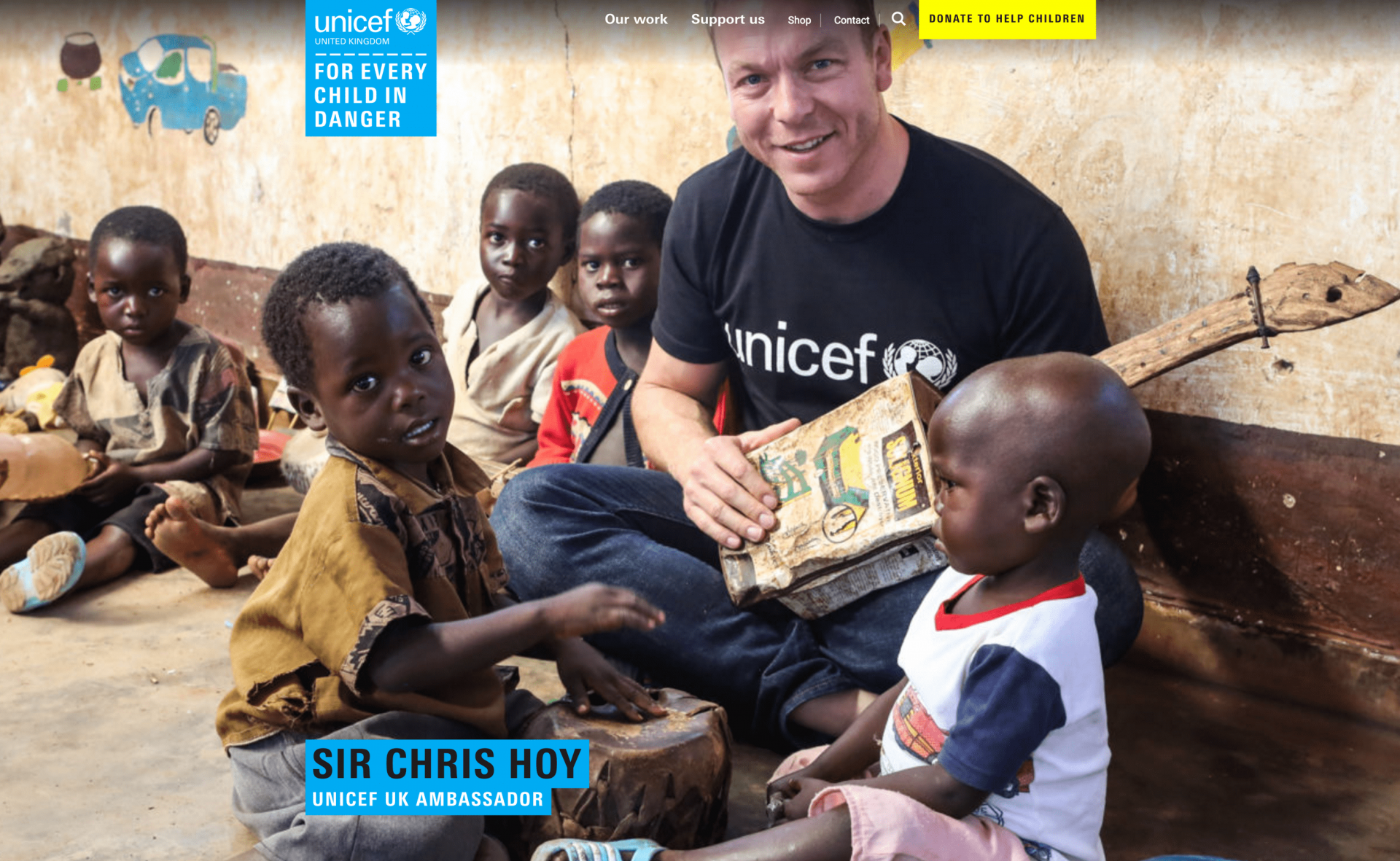

Messenger

Who communicates information makes a big difference

We give credence to information depending on who we perceive the source of that information to be.

We are generally well disposed to those we think of as authorities on the subject, and those we know, but will discount information from those we don’t like.

So it’s important to make sure that people identify with the messenger as much as the message.

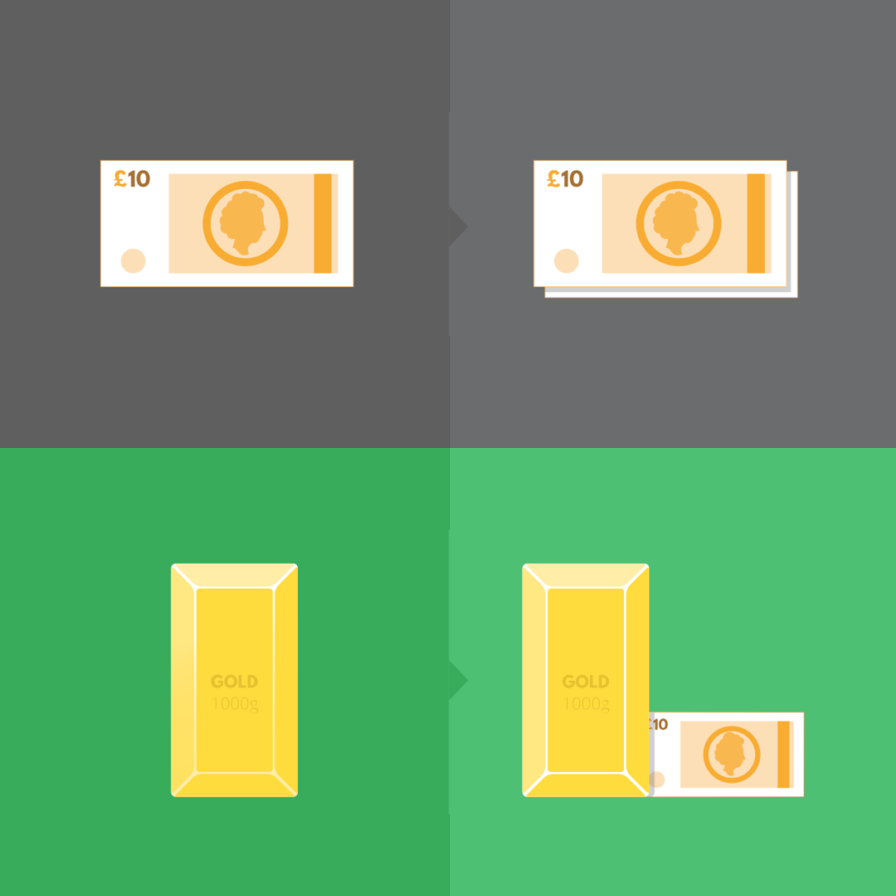

Incentives

Predictable mental shortcuts influence our response to incentives

People don’t make detailed cost benefit analyses when making decisions, and often revert to simple rules when weighing up what to do. For example:

Losses loom larger than gains

– The prospect of gaining £10 is a lot less motivating than that of losing exactly the same amount.

Reference points matter

– A gain of £10 is huge if its compared to £10, but negligible when its compared to £1000.

Small probabilities draw disproportionate attention

– Which is why people buy Premium Bonds, and play the lottery, even when they ‘know’ they odds are not in

their favour.

We allocate resources to mental “budgets”

– 1/3 off a £15

t-shirt is worth the effort, but £5 off a £250 handbag isn’t.

Today crowds out tomorrow

– we’d much rather have £10 today, than £11 tomorrow, thank you very much.

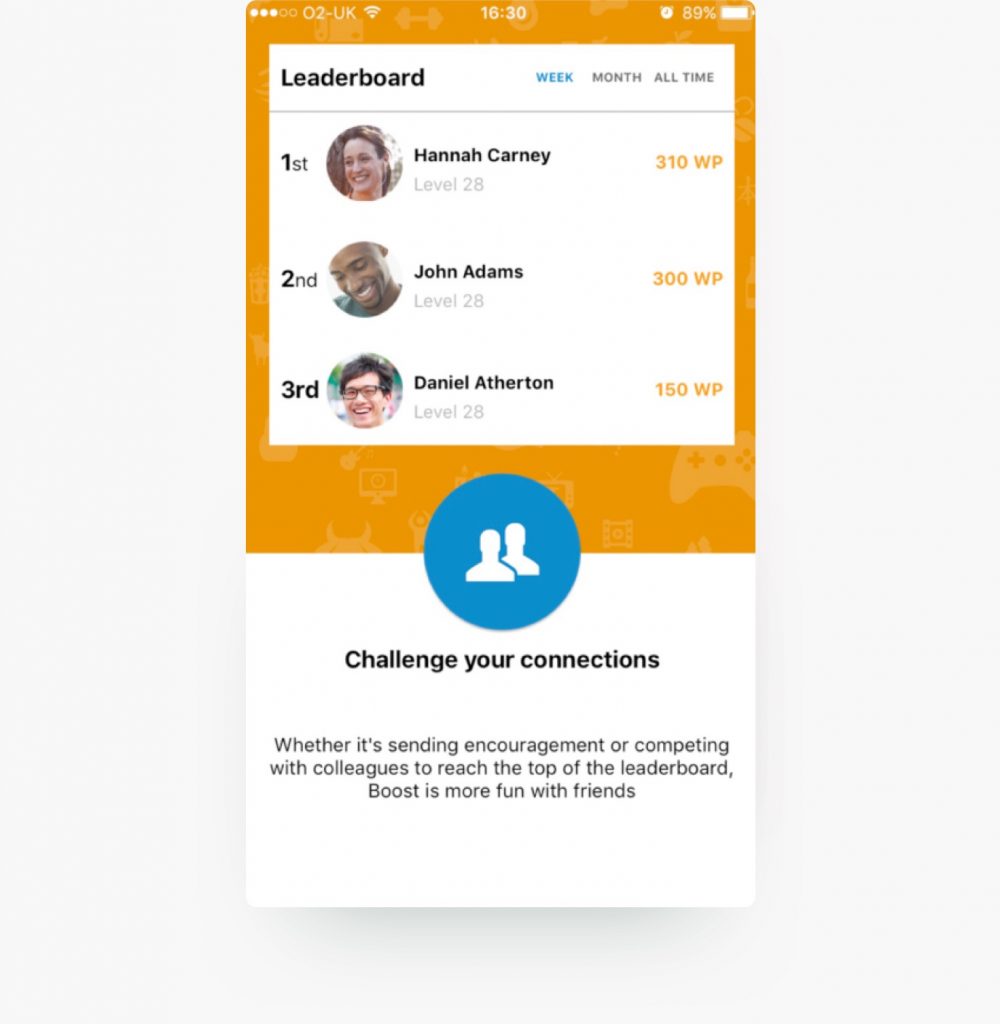

Norms

We do what people around us are already doing

Humans are intensely social creatures and take their cues from the perception of the behaviour of those around us.

If you can make clear what others do in the same situation, that can influence the choices people make, and if you make it clear that people like you do this, people are even more likely to conform to the perception of the expected standard.

Presenting the expected norm is a hugely influential means of inculcating a desired behaviour.

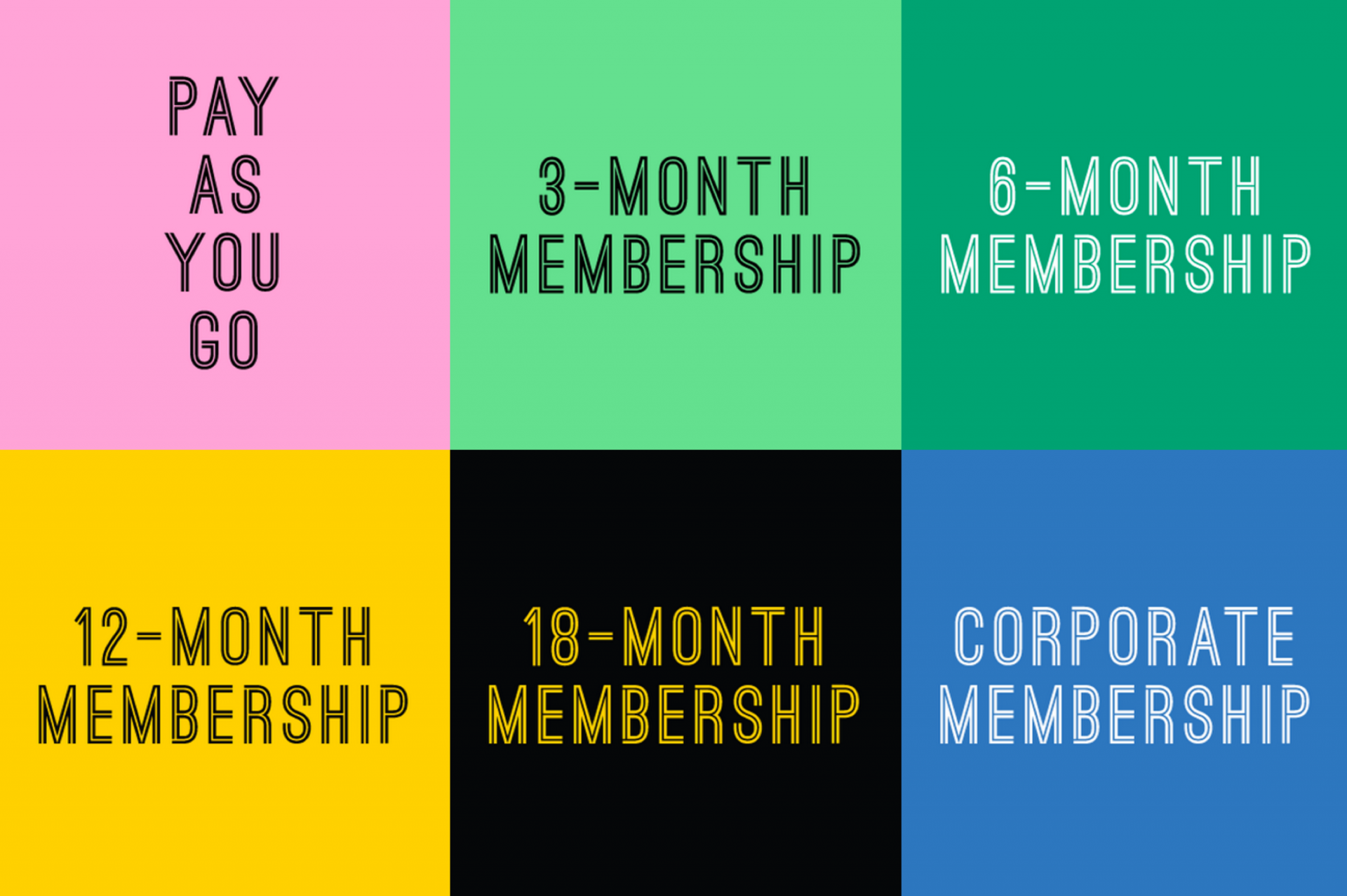

Defaults

People tend to “go with the flow”

Because people are time-, attention- and effort- constrained, people often find it preferable to simply do what’s an option that’s pre-selected for them, even if that option is doing nothing, and even if that choice to do nothing has a significant associated cost.

Structuring the default option to maximise benefit makes the right choice the easy choice, without restricting other choices on the user’s part.

Choice architecture is a hugely important tool in behaviour change, and should never be overlooked in the structuring of even the simplest options.

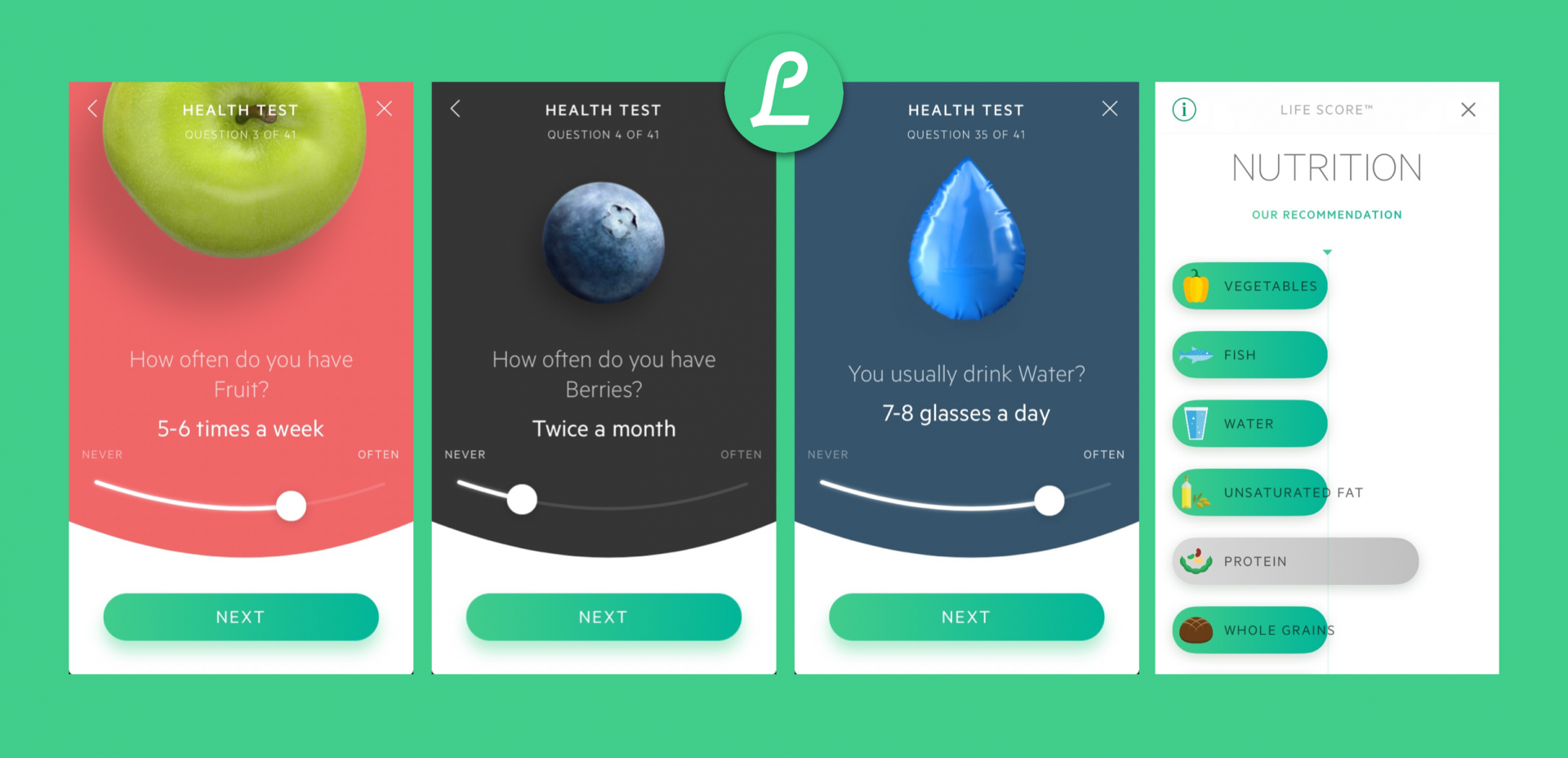

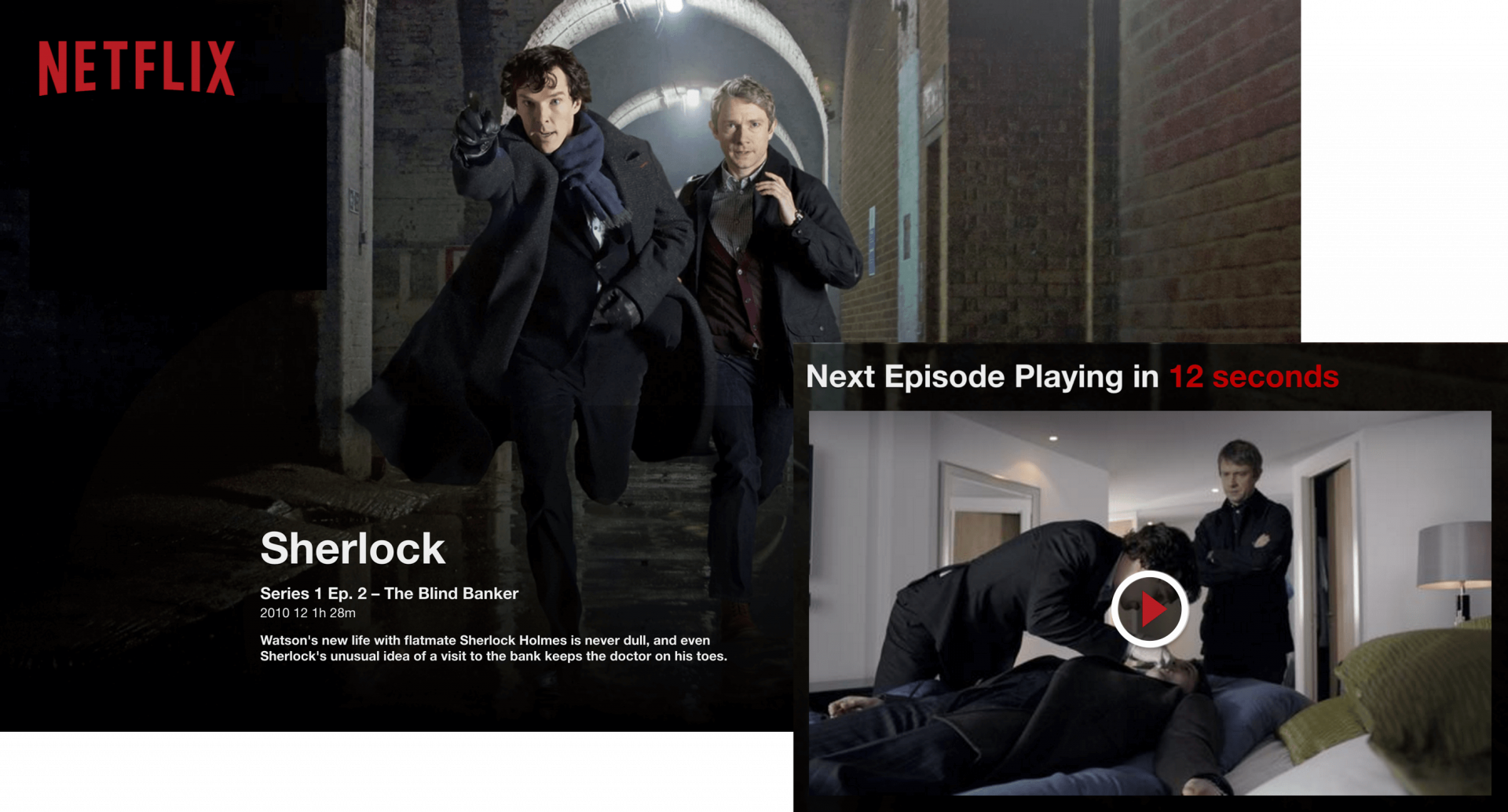

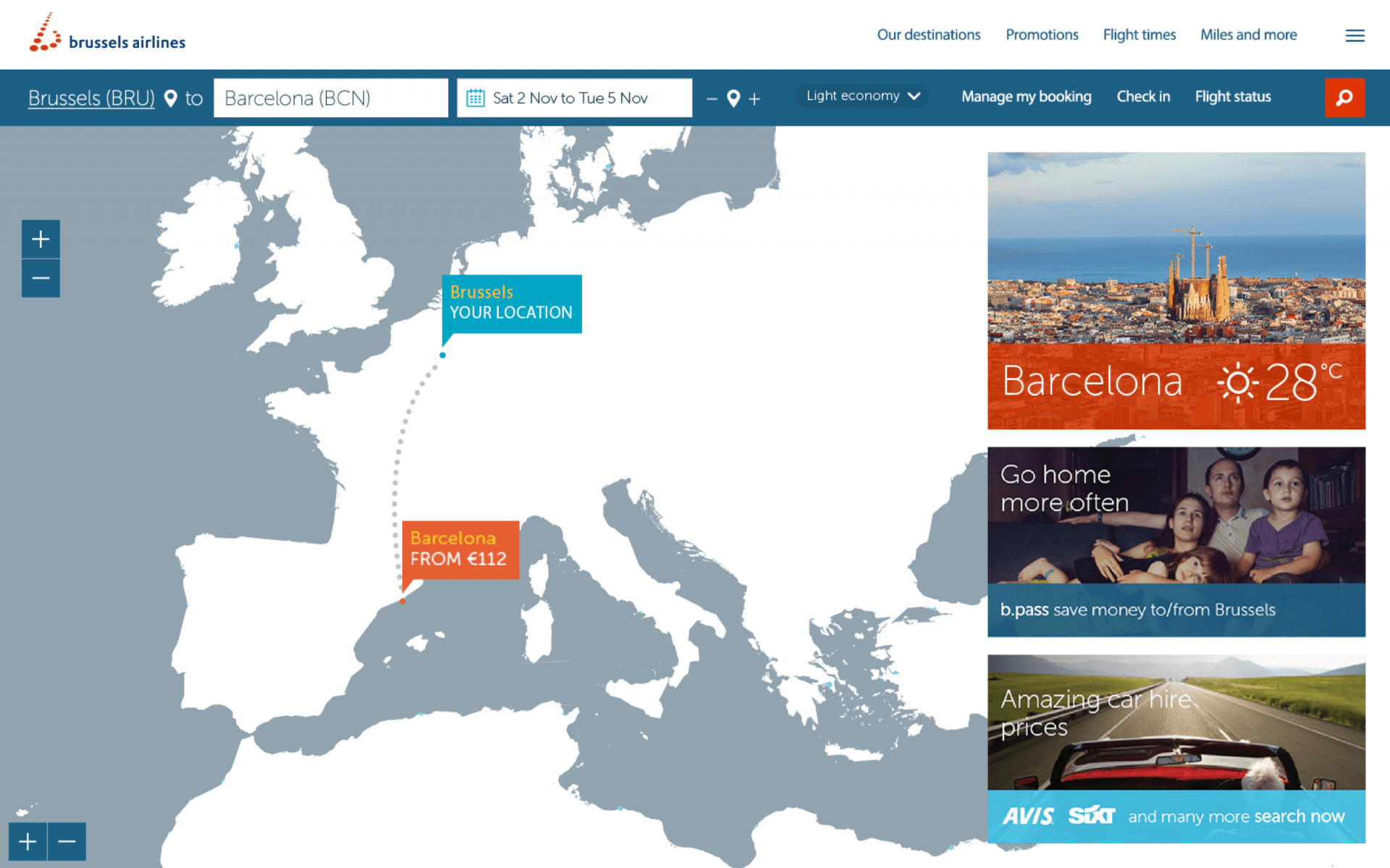

Salience

Attention gravitates towards the new, the relevant and the simple

Our attention is the single most prominent factor in our decision making – without attention on the choice, it simply won’t be made, often leading to poor outcomes.

Constantly bombarded with stimulus, we filter out as much as we can to cope with the unending flow.

But our attention is drawn to the novel, the accessible or the simple.

Of these, simplicity is perhaps the most important – presenting choices in a way that we can quickly relate to and grasp in terms we personally understand allows us to make decisions much more quickly and effectively than the same choice couched in more general terms.

Making the right choice bold, visible and personally impactful helps drive the desired response.

Priming

Sub-conscious cues influence behaviours

Humans are a lot less rational than they like to think – to the point that things they don’t think about are often as important as those they do.

For example, ‘situational’ clues, like the placement of running shoes, or healthy lifestyle magazines, will lead to people choosing ‘healthier’ options in certain circumstances.

As the effects are subliminal, it’s often hard to predict exactly how such collateral influences shape a person’s decisions, but it is important to consider these effects, if only to have made best effort to avoid including that might drive an aversion to the behaviour we wish to instil.

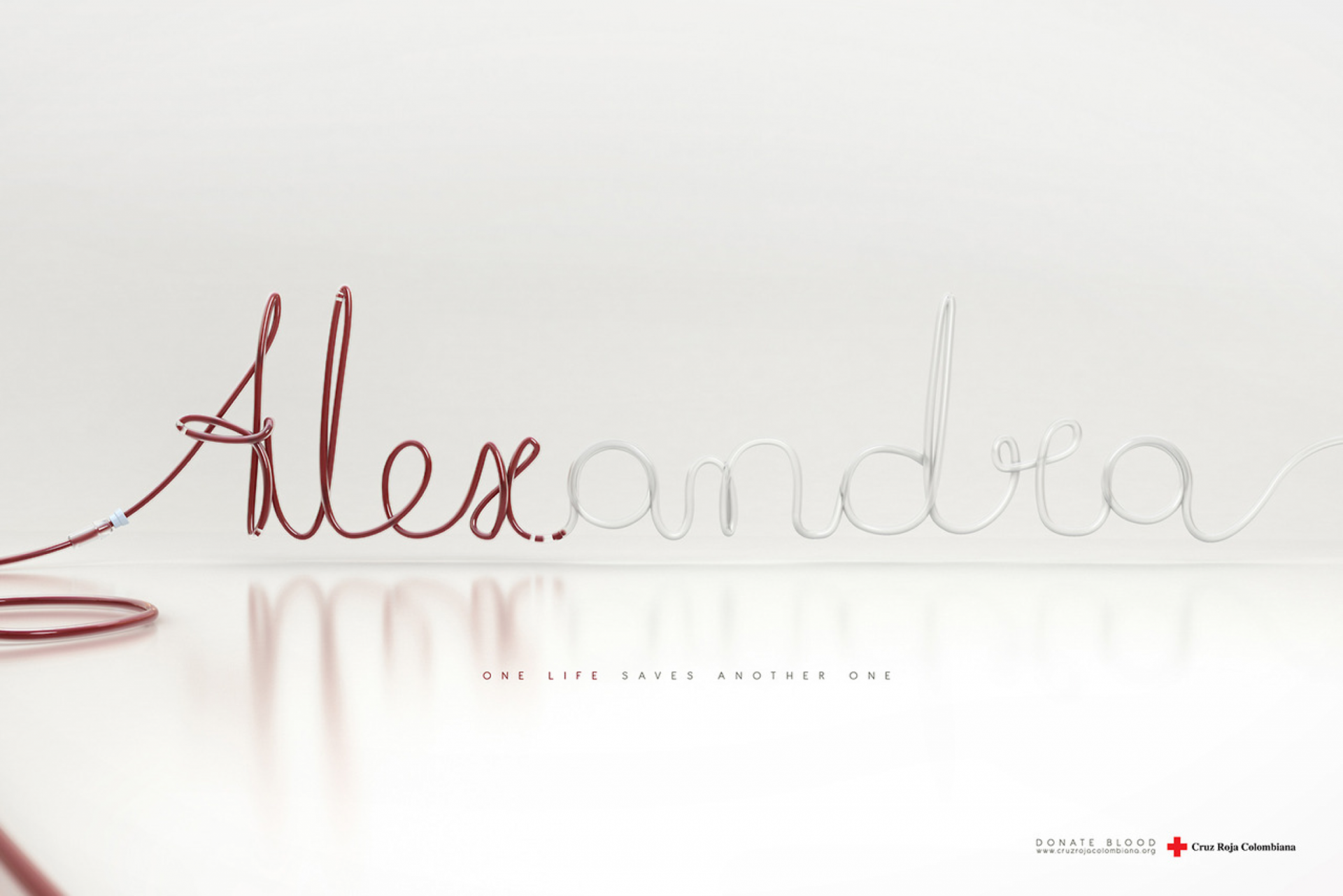

Affect

Emotions drive decisions

We think that our emotions are under the control of our reason, but really it’s the other way around; reason serves our feelings, by helping us determine how to achieve what we feel most valuable.

As such, evoking the right emotion at the right point in the decision-making process is an essential component in any behaviour change programme – so long as someone can see how their emotional reaction can be addressed by the options presented.

Indeed, mood itself is a key driven of certain decisions, so we design experiences as entire wholes geared to create a positive interaction with an organisation, and dispose the user to the positive choices presented.

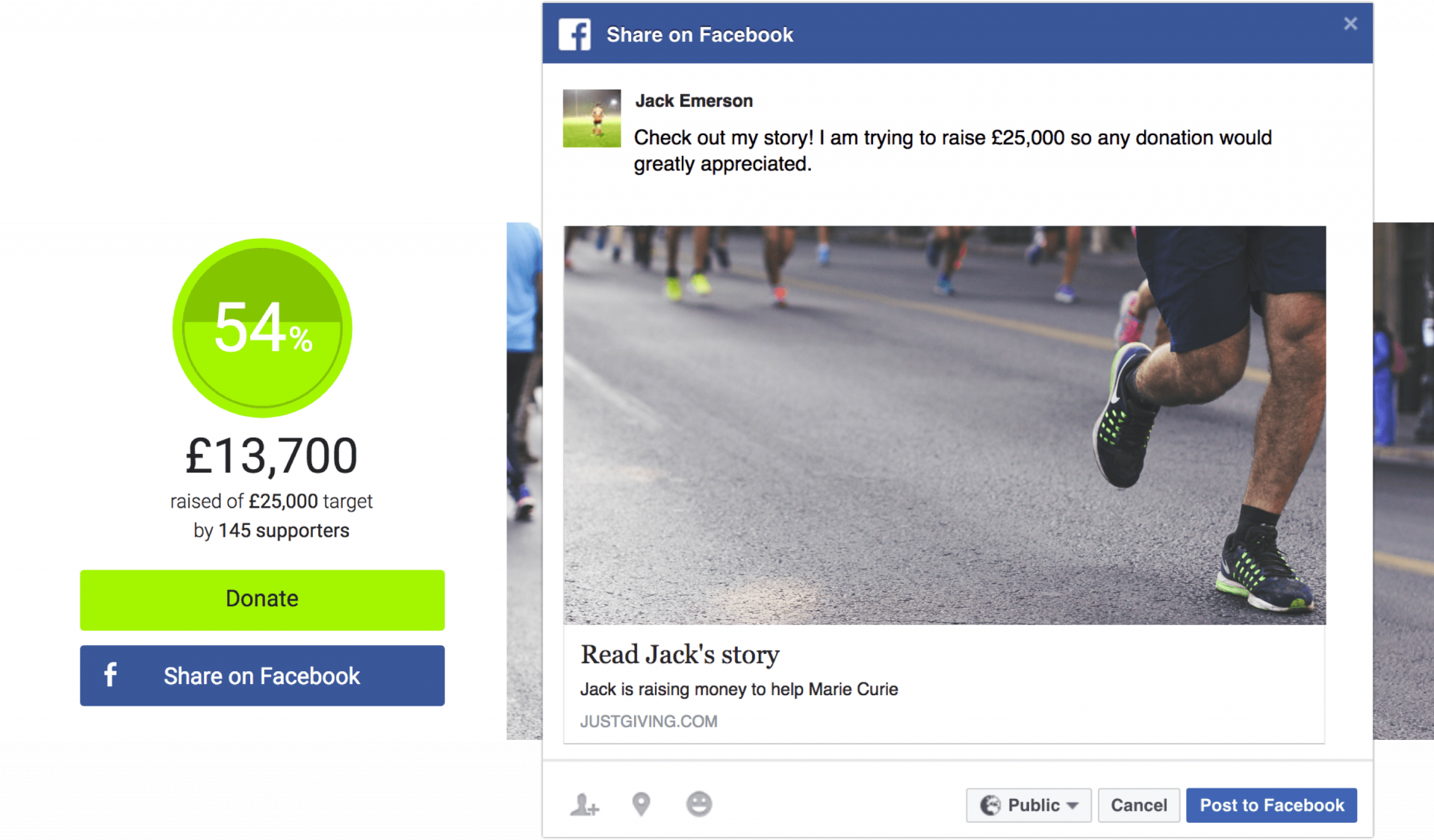

Commitment

We want to be seen to keep our word, or return a favour

Humans like to be seen as consistent – so they’re much more likely to keep promises publicly made.

And they like to be seen as fair in their dealings with others – so they’re very likely to return a perceived favour or gift.

Both of these inbuilt sentiments provide a powerful mechanism to change behaviours – if help people make a public commitment, they’re much more likely to stick to the committed goal; if we give them a gift, they’ll work hard to ensure that they’re seen to repay in similar kind.

Ego

We do what makes us feel better about ourselves

People like to have a positive and consistent self-image, and will go a long way to maintain it.

For example, once they’ve made some small alteration in their behaviour, they’ll often commit to a larger change – to the point that they’ll alter their explicit attitudes and opinions to reconcile with the things they’ve newly done.

Indeed, when beliefs and behaviour clash, its often beliefs that are adjusted – putting paid to the theory that to change behaviours you must change attitudes; it is often precisely the other way around.

As such, encouraging a small change, and then reinforcing this be reminding people of it, can be a much more powerful way to change behaviour than any form of persuasion.

Equally, creating a positive expectation of change creates an internalised self-image, making success a much more likely outcome.

Both of these techniques can exact powerful results in customer behaviour.