The blindspot of design systems

Watch your language

Recently there has been a lot of buzz around design systems because of the value they bring in enabling teams to design and build better products by streamlining workflows and making assets reusable, scalable and more consistent. Design systems though are not just for designers.

The majority of the literature available has been focusing on the core target audience – design practitioners within product teams. There are however other parts of a business, that are integral to the final delivery of these experiences and they are often neglected.

One of these groups for example, are content creators.

As well as addressing the immediate needs of the product team, design systems should also be able to support marketing activities and any other strands of the organisation responsible for generating original content for publishing.

To do that effectively, during the planning phase of a design system, our scope needs to cater for addressing multiple audiences. Brand elements, components, patterns etc… are still all relevant, but a solid design system should include user guides written at different altitudes that are comprehensible, actionable and can be expressed across any touch point.

Language needs to cater for all relevant audiences within an organisation and in most cases they have different backgrounds, skillsets and level of understanding. The jargon terminology used by expert practitioners can sometimes become a barrier to entry to other audiences.

The answer to this challenge is not simplifying the language to the lowest common denominator but to tailor the relevant parts of the design system to each audience.

For designers

For one of our clients, in addition to working files in Sketch and a module catalogue in Adobe Experience Manager, we delivered a design system handbook tailored to the product team.

For content authors

Other members of the organisation that had a direct involvement with authoring content, were supplied with a task oriented authoring guide.

The design system as a product

Before design systems, organisations relied solely on brand guidelines to inform teams that created products and services. Sadly, one of the main misconceptions at the moment, is that a design system is a glorified an augmented brand guideline document that includes digital elements.

Although partly true – because it does that as well, a design system is a very different beast. Where a brand guideline document is perceived as a finished good, the design system is a living document. Its update cycles are more frequent – evolving as the product evolves per release, maybe even per sprint.

Its format is also more fluid. Instead of being delivered just as a read only experience, a design system can have multiple instances in an ecosystem that serves different sets of users. For example it can exist as a sketch file for designers, a set of codified elements for developers, a set of PDF guides for specific users or a web portal for general reference.

In a way, a design system is a product in itself. And as a product, it should be scoped as such, be governed, given the right conditions to evolve, grow and have its performance tracked over time.

There are three key performance indicators that a design system needs to deliver against:

- It needs to make creation and production cycles faster (speed).

- It needs to make it easier to manage design streams in large teams – who aren’t necessarily all in one location (consistency).

- It needs to make it easier for employees outside the product team to author and publish content.

Finally, for a design system to succeed, enforcers champions need to be appointed across the different skills (content, brand, product, marketing) that can promote adoption and make critical design decisions. If an organisation doesn’t have these roles, then they must seek expert help to plug the gap.

In the following sections, we are going to take you through our approach for planning and delivering design systems, and then we are going to touch on some key areas like communicating invisible value and the cost of ownership, that are usually a blind spot for design consultancies and organisations respectively.

Design systems

Our approach

Planning for success

There are three things that we take into consideration before planning for a design system:

- The size of the product / ecosystem of products that we are designing for.

- The primary and secondary users of the design system, their intra and inter-team workflows – as well as their aptitude.

- And finally the delivery method and distribution channels of the system.

Defining the product scope

When it comes to scoping, one of the considerations that will define the phases of work is whether we are dealing with a new or a legacy product.

New products usually have less defined scope and their roadmap is prone to changes. Delivering a system with a lean design approach might be more suitable as it allows teams to be more flexible and agile without being too prescriptive.

In this scenario the system evolves as the product grows and becomes an integral part of the development cycles. The main challenge in this case is not how the system is set-up initially, but how it gets updated, synchronised and re-distributed.

On the other hand legacy products – while they give a better indication of total scope – are usually plagued with inconsistencies. In our experience this is usually when organisations come to the realisation that they need a better system to manage their product and content creation processes.

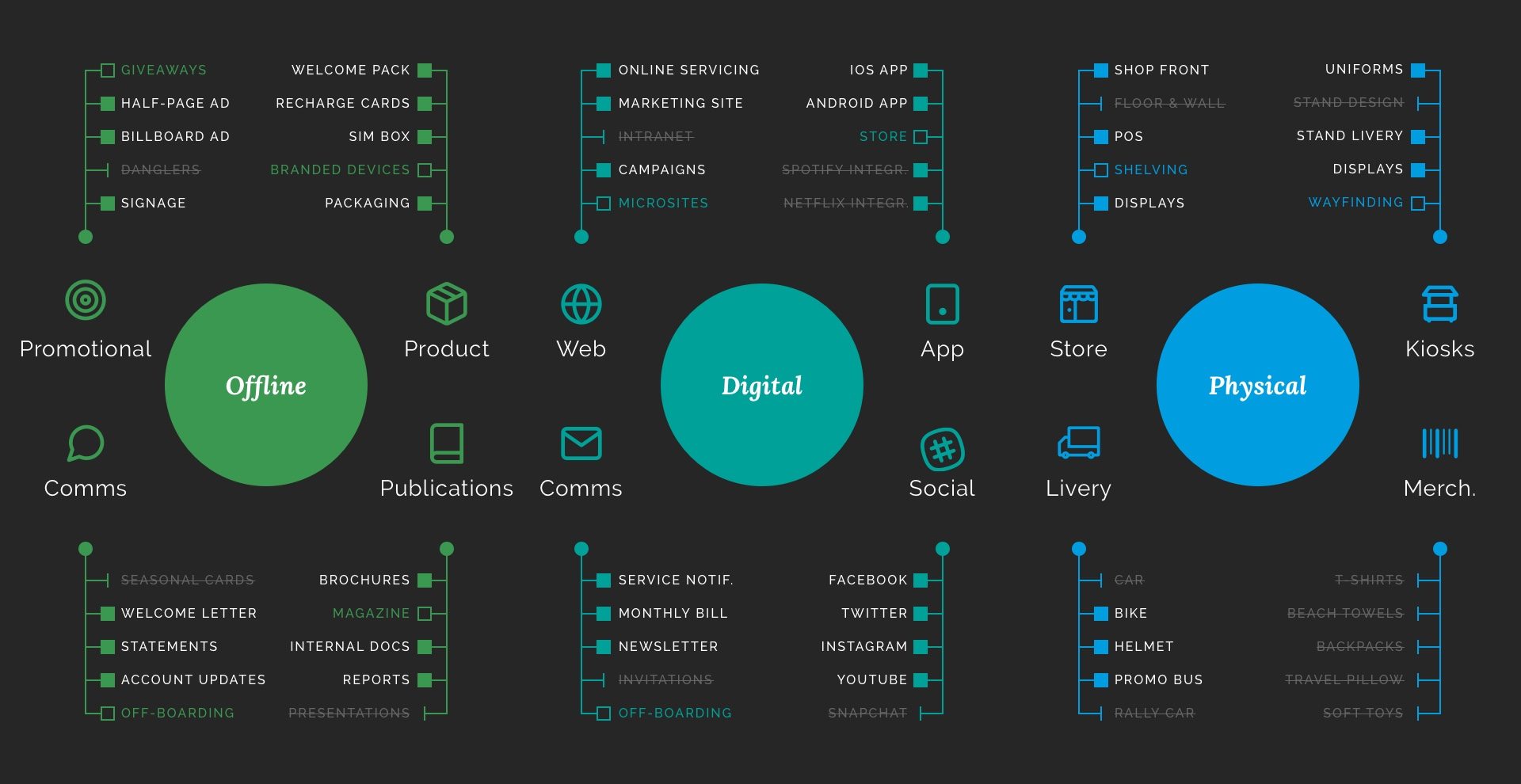

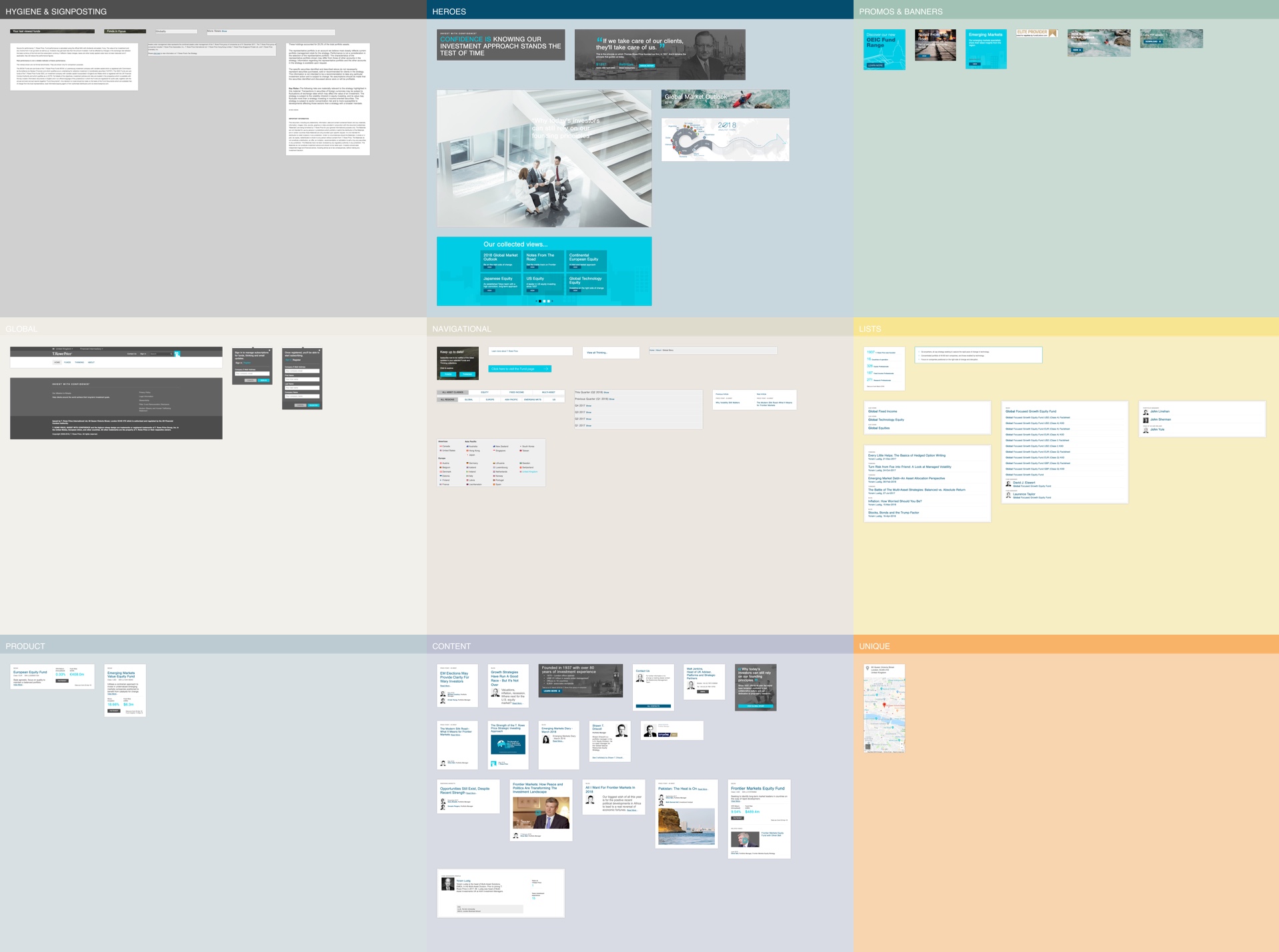

To evaluate the extent of the challenge, we need to look at how vast the ecosystem is and assess the channels of presence. To do that, we conduct a visual audit across all channels and start mapping out the main clusters of components needed to construct the kit of parts of the system. We then look at the product roadmap and identify any possible gaps that need to be addressed immediately and for near-future releases.

Understanding the audience

Design systems are not just for designers. If you take a macro view of a product’s lifecycle – from early stage prototype to in-life – there is a more diverse set of users that are going to interact at some point and to some degree with the system.

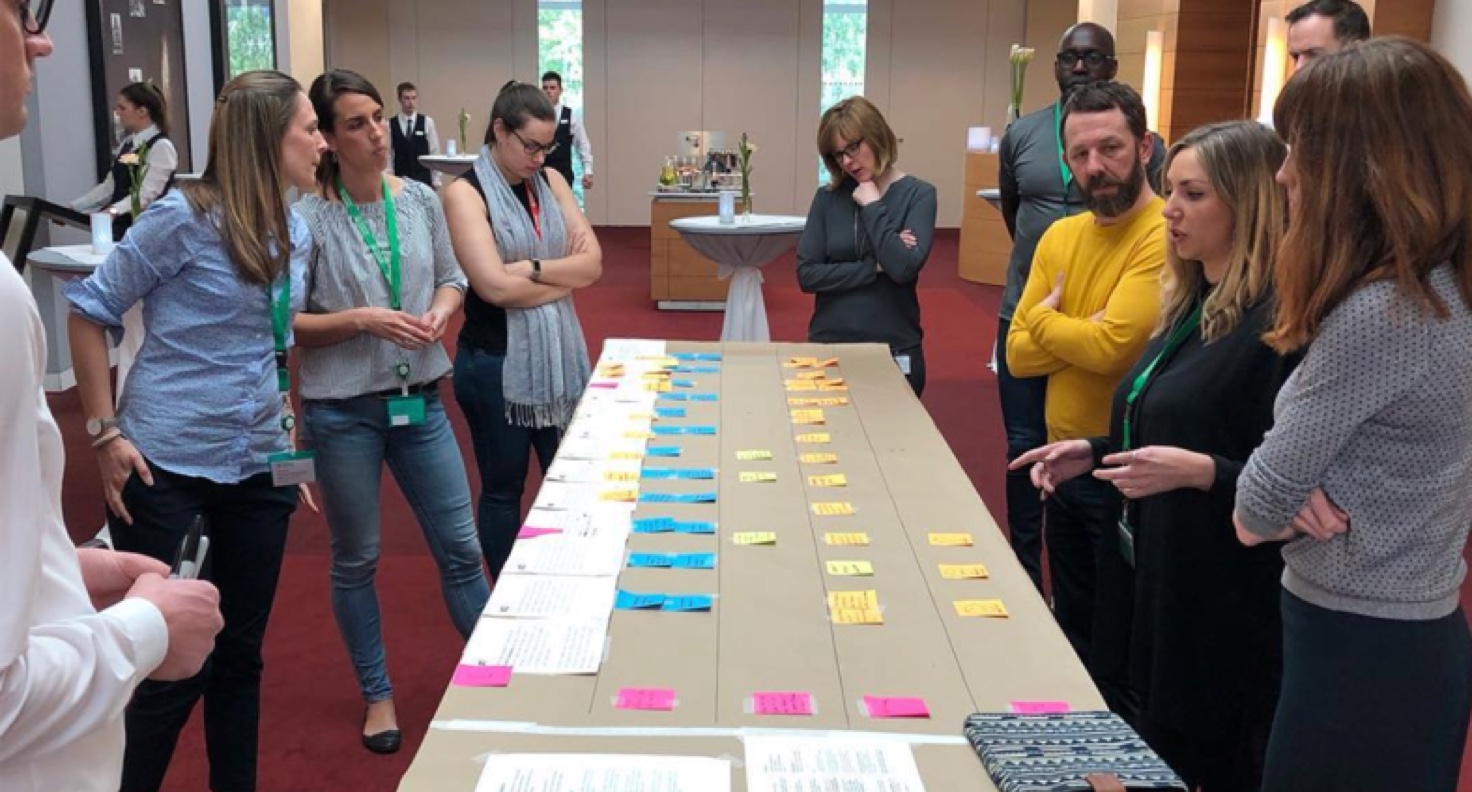

In order to understand how a system can benefit specific user groups, as well as improve collaboration between them, it is important to spend some time empathising with their workflows. What tools do they use to create design artefacts and content? How do they communicate with each other? How is quality assurance handled? How is content authored and published? What are the main challenges they face in their current processes?

By conducting group workshops as well as one-to-one interviews with stakeholders and practitioners, we can start mapping out requirements, inefficiencies and dependencies and start creating alignment within and between teams involved in the process.

The challenge here, is that it can become very political and in many cases a rant-fest. But remember that storming, is a precursor to norming and eventually performing. If this part is neglected and brushed under the carpet, there is no design system on earth that can solve deeper team communication issues.

So a design system, in order to become effective, should not only be treated like a product – it also needs to be accompanied by a set of behaviours that promote collaboration through better communication.

Building a foundation

A design system at its simplest form is the rationalisation of rules that govern the creation process of any type of artefact related to a product. To build a system that is truly scalable, rules need to be layered on top of a foundation that is coherent and consistent. We build this foundation by answering the three following questions:

- What are the brand’s core assets?

- What should the end user’s experience be?

- What are the brand’s ownable moments?

Brand audit and initial exploration

When dealing with already existing products, identifying the core assets within an already established brand is a bit like the process of moving to a new home. Actually it’s a bit like the moving out part. You don’t just toss everything in boxes and tip them over the other end. You need to get everything out, have a good clear out – and to find what is truly essential, you need to be ruthless. In other words we need to think about what still works, what fits and what needs to be cast aside.

The benefit of this process is that it removes all the legacy clutter. With all the noise gone – while still being respectful of the underlying principles by which the current system lives – it allows us to initiate a design exploration unbound by the current visual and written representation of the product.

From brand values to experience takeaways and principles

Every brand guideline document ever written comes with a set of brand values. Brand values are a great tool when it comes to giving teams a sense of purpose, defining their behavioural integrity and setting a point of differentiation when compared to other brands.

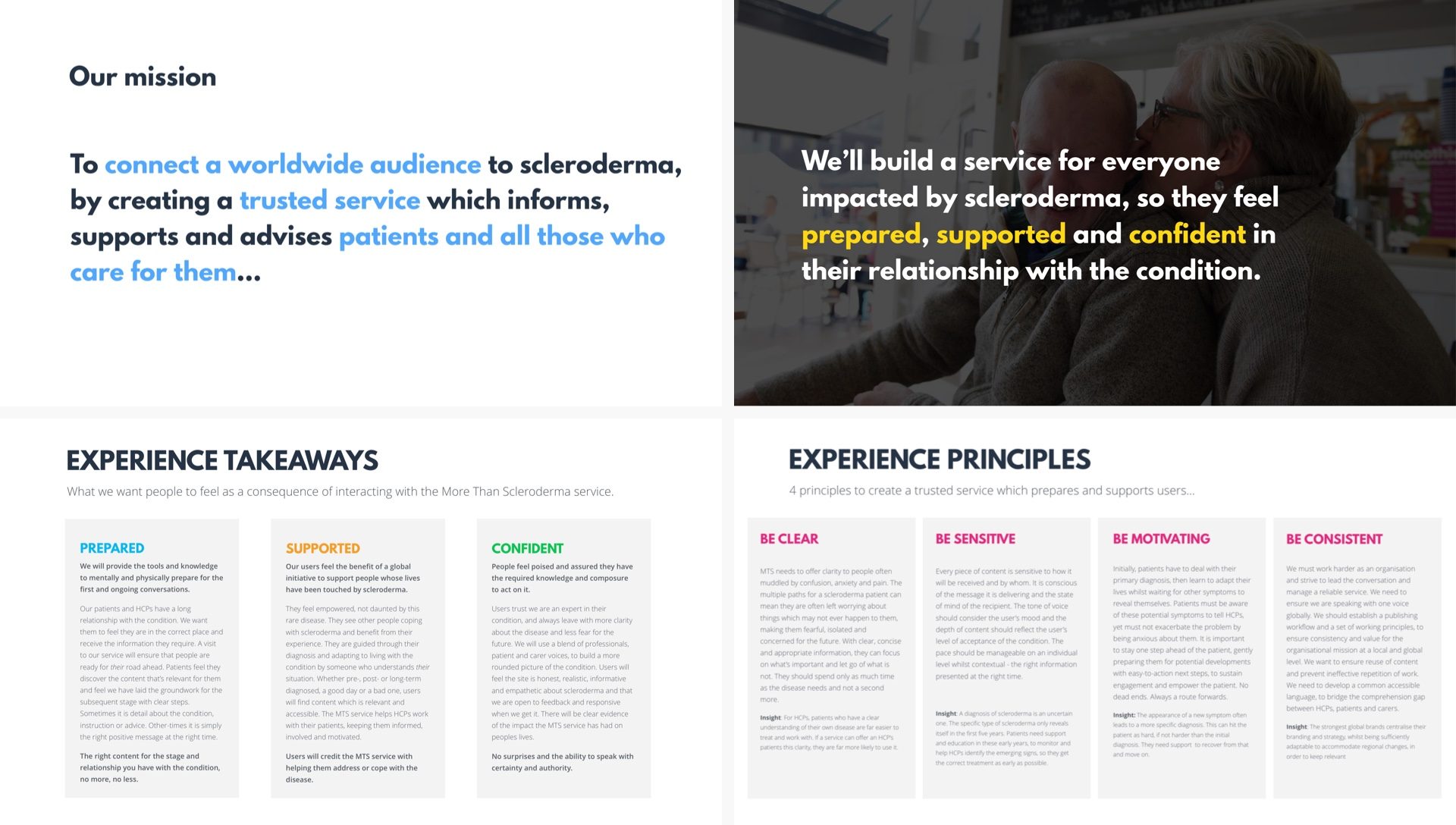

When crafting experiences though, these values can sometimes be a bit too packed and that can lead to confusion as they can be interpreted in many ways. To mitigate this, we find it helpful to turn those values into tangible actions. We first define the set of feelings that we want our users to remember as a result of interacting with us, and secondly we find the right mechanisms that will allow us to deliver those takeaways.

But how does that percolate all the way down to a decision in the design system?

Well let’s take as an example, that one of our brand values is ‘Trusted’. Our respective experience takeaway could then be: ‘We build a service so that our users feel prepared, supported and confident’, which in turn could evolve to the following principles: ‘To deliver that, we need to be clear, sensitive, motivating and consistent’.

Now if we focus in just one of these principles we can see how that grounding exercise can inform our decision making process when designing the system. Being ‘sensitive’ could affect the choice of photography, tone of voice, as well as help us orchestrate the depth of content delivered at specific points in the experience so that we are able to deliver the right information at the right time.

In three steps we have gone all the way from top level brand values to experience takeaways and actionable principles that have a direct effect on the way we should be designing our components, modules and content.

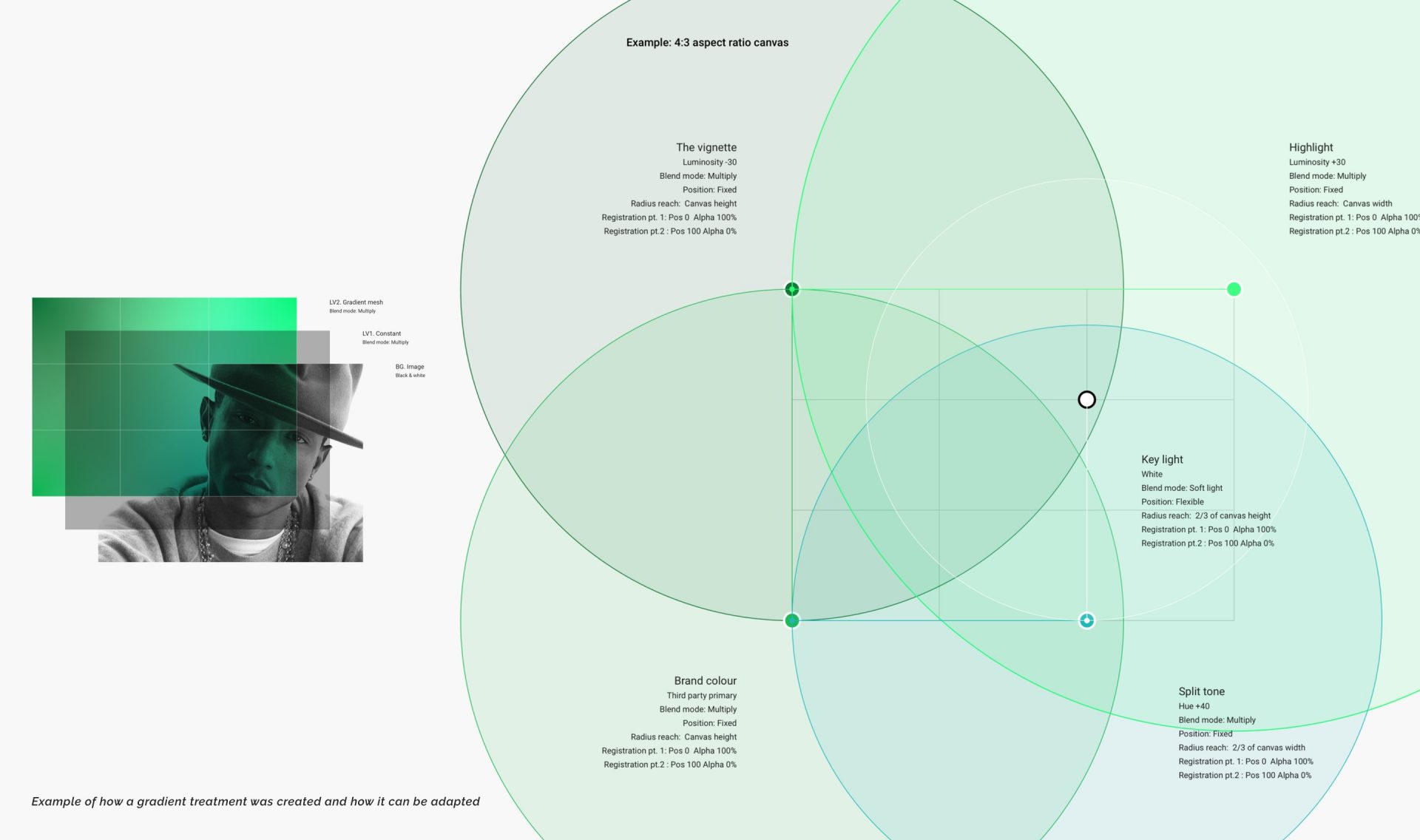

Ownable moments that deliver the emotional takeaways

The final step is to identify a brand’s ownable moments. Well conceived design systems are all about doing the basics brilliantly (buttons, forms, navigation, information design…) but also about creating opportunities to express the brand in its own unique way and deliver the emotional takeaways in key interaction moments. These might be for example when a user has finished onboarding, or when funds have been invested, or when one has successfully completed a key task.

Having a clear view of what these key moments are and crafting the experience around them, we can avoid the risk of creating sterile cookie cutter design systems and create something unique for the brand.

In lieu of time consuming user journeys, we find that it’s more effective to create user stories that give a general indication of context and craft carefully selected moments in more high definition visuals, animations and micro interactions. By doing this, it allows us to get a feel not only for how we want a brand to look but also behave – which will influence how the building blocks for our components will eventually be crafted.

This top-down approach is not necessarily in conflict with atomic design methodology. It supplements it by giving a sense of general direction of travel.

Building the environment, the building blocks and the team

Setting up the environment

Setting up the environmental rules is the most technical aspect of the system, the most important and also the most invisible to clients. A good analogy would be a comparison to video games. On one hand you have your game objects. Those are your character, your weapons, your vehicles etc… Those are the things you can see. What you can’t see though, is the game engine that defines how all these elements behave and interact with each other.

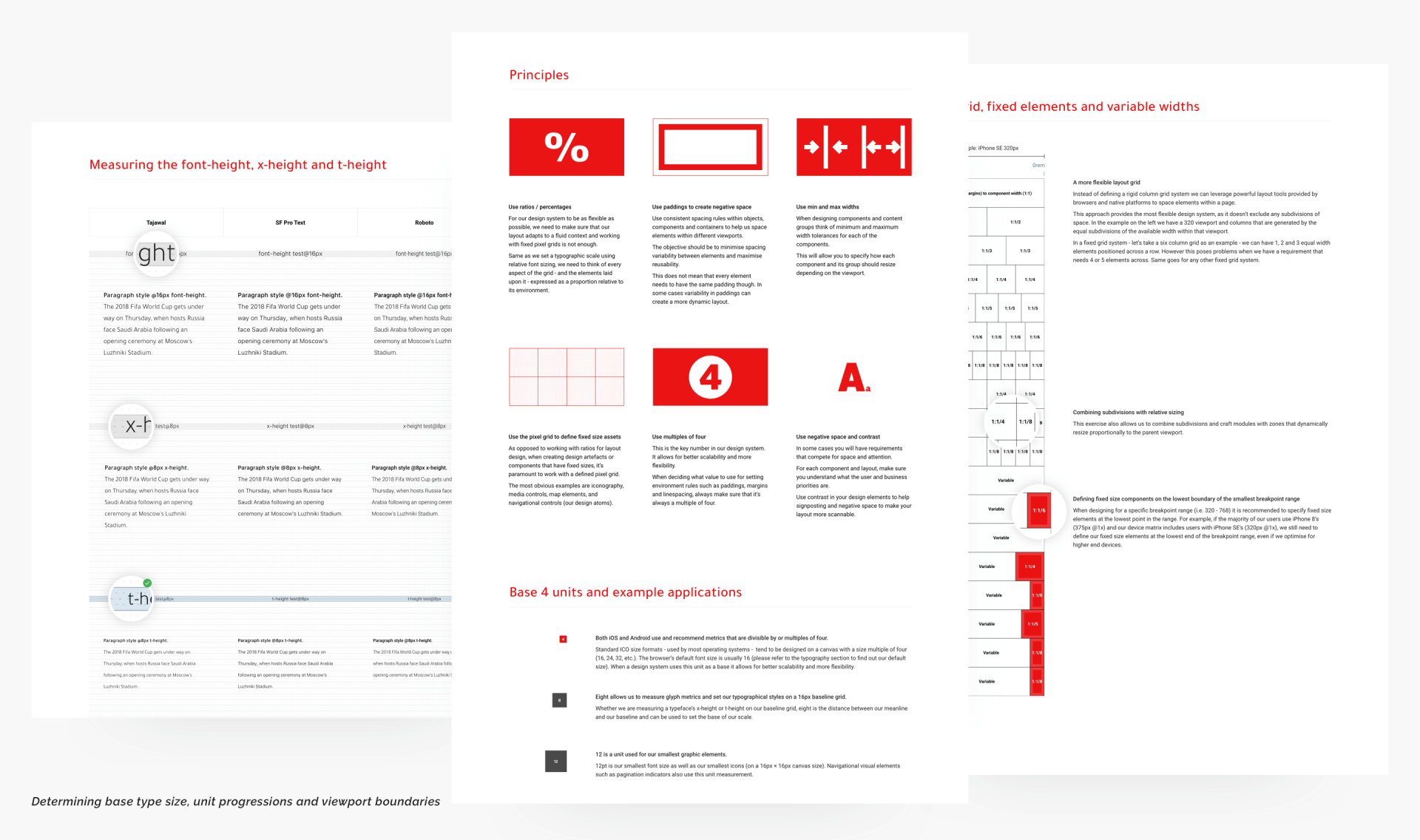

At this point in time we would be setting the system’s base unit that will allow us to derive spacing values, we would look at the device matrix to set our responsive framework and start having a feel on minimum and maximum sizes for certain elements. During the set up phase we will also generate tools like a baseline grid, potential type scale progressions, and also test colours for acceptable contrast ratios depending on the accessibility requirements.

This might not sound like a lot but if enough time and diligence is invested at this phase it can save you lots of time down the road by removing guess work and minimising scalability issues.

In one of our most recent projects for example, when we were testing type scales, we used three different font metrics to help us set typography: the x-height, cap height and t-height. This produced three sets of sizes based on the same progression. Selecting the right one was about experimenting with a good sample of components and choosing the one that was the most scalable.

Setting up the components

By using an atomic design methodology we can then start creating a system’s components from the bottom up. Starting with the lowest boundary in our responsive framework we can start defining minimum sizes for our atoms, set fixed and flexible component zones and define spacing rules in a more granular way.

The process here is simple. Design, test, adjust, consolidate, move on to the next and repeat.

Setting up the team

A design system in the product development phase – no matter how extensive it is – is always going to be incomplete. Assets will be missing and others will need adapting over time.

However, when delivering a system to other teams we find that the most important aspect is not the assets and components themselves but giving the design teams the technical know-how and tools to create new or adapt assets to meet future needs. This is when a system works as intended and transcends the boundaries of a brand guideline document. What’s that saying? ‘Give a man a fish…’

Design systems

The blind spots

The invisible value

Delivering design in the form of templates, module catalogues and prototypes is one thing. Clients are accustomed to that. They can see the result, comment on it, give feedback and see how it will eventually come to life.

Delivering a design system is a bit trickier.

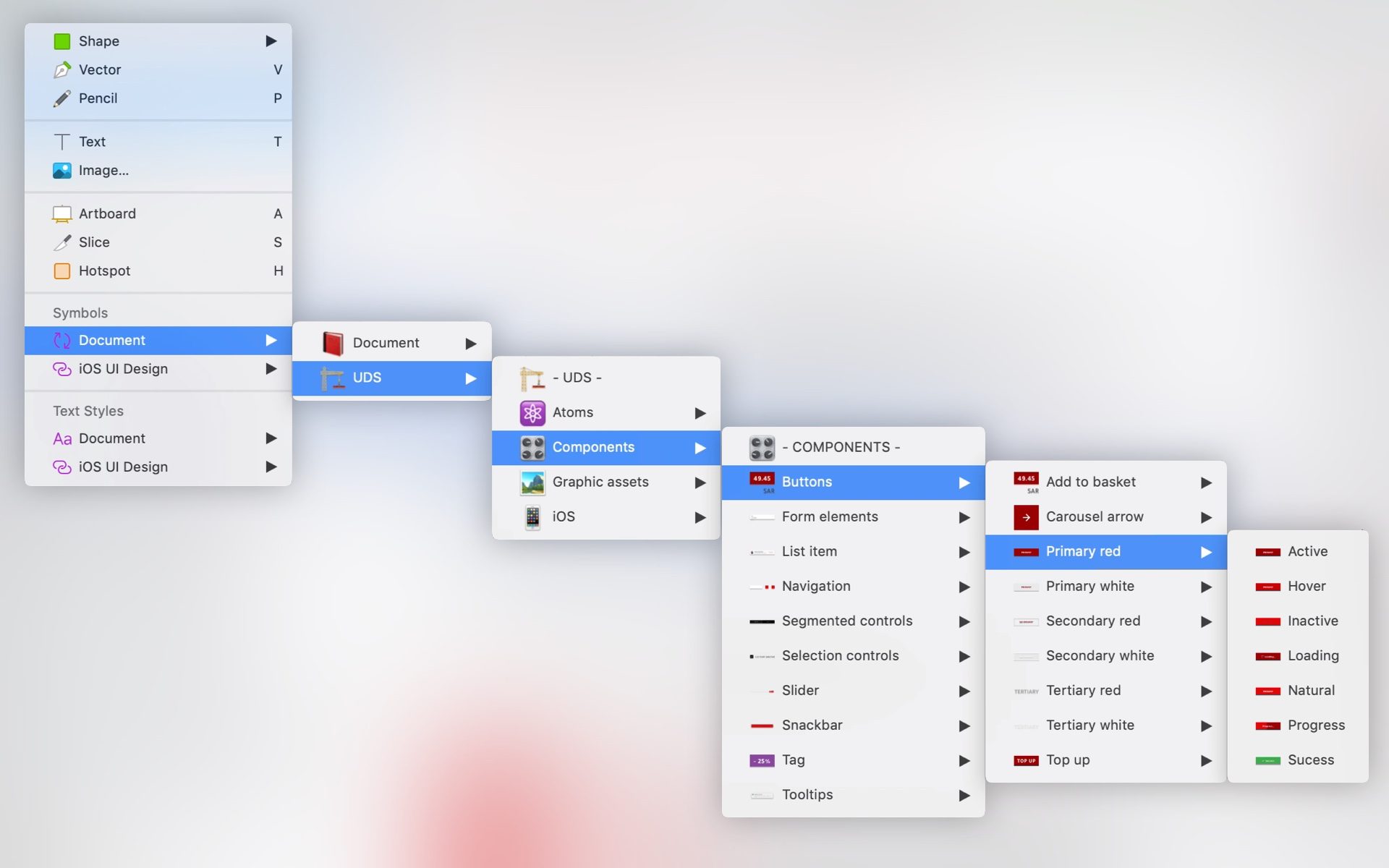

For example, in another recent project, we identified that the main reason behind the design inconsistencies within the product, originated from the fact that the multiple product teams within the organisation didn’t have the same workflow set up.

So we decided to mitigate that, by customising their Sketch workspace to have all the necessary styles, palettes, symbols, components and treatments readily available in the menu system by substituting application defaults. In this example we also provided sample applications to help designers understand how all the elements came together. But even if the file didn’t include those examples and was completely blank, it would still be very valuable to practitioners, as it removed all the cumbersome task of setting up a new working file and risking creating inconsistencies.

The challenge for agencies is how to communicate to stakeholders the value of the inner workings behind the visible layer, when they are not practitioners themselves?

At ELSE we found that the only way around this is to make sure that all target audiences are part of the process.

Remember of the analogy of the design system as a product? Well the development process is very similar as well. We look at the backlog, set sprint goals, and demo at the end of each sprint. These discreet package drops, allow us to showcase what’s hidden under the hood, by including all relevant stakeholders in the journey, and make sure that value is perceived collectively.

Underestimating the effort of implementation

Acquiring a design system is a great starting point but how does it get adopted and propagated within the organisation? In a way, creating the set of rules and the kit of parts is the easy bit. Getting everybody on-board and using it is a whole different ball game.

The size of the production team, as well as how that team is geographically distributed is proportionally related to the effort needed to applying and maintaining a design system. The bigger the team, the harder it is orchestrating its implementation. Are there any language barriers? Do certain elements need to be localised?

To truly leverage the value of a design system you need to be prepared to factor in the time and investment to get all relevant teams trained to use the system effectively and put in place the right processes and channels of communication.

As we said before, adopting a design system needs to be accompanied with the right set of behaviours. And behaviour change is very difficult to achieve. To break away from old habits and make space for new ones, you need to make a conscious collective effort.

Getting external help – that is impartial to the internal politics and doctrine can also help you instil the right behaviours until they have solidified and have become the new modus operandi.

The true cost of ownership

So, you got a design system, tick. You started implementing it, tick. Now how do you maintain and extend it? Hmm..

When dealing with multiple teams working across multiple work streams with a single design system there is the danger of one or more teams getting to a gap overlap in the system. For example, let’s say that we have team A working on the product’s website and team B working on the app. A new requirement comes in to develop some new cross-platform functionality and the two streams need to deliver it concurrently. How do you synchronise effort, ensure experience consistency and maintain a single source of truth?

Option one is, you focus on go-to-market speed. You launch with potentially two different experiences on different platforms, align design at a later date and update the design system with the new patterns and components.

Option two is, you focus on consistency. So you develop at the same time, test, align, launch a consistent experience across platforms and then update the system.

Option three is, that you don’t run into that problem at all. Your backlog across all work streams are monitored in the scrum of scrums and gaps are anticipated in advance. New functionality requests come in a predictable manner, the design development happens collaboratively and the design system is then updated and redistributed.

Theoretically that sounds simple but in order for that to work, you need to have buy-in from more than just the design team. Product owners, business analysts, scrum masters, developers, content creators, researchers and everyone involved in bringing the product to life need to be on the same page. Orchestrating that, is not a simple task.

The point here is that the true cost of ownership is not monetary, it’ s cultural – in the form of organisational re-calibration. If you want to benefit from a design system, you need to pay the price.